01. Sophisticated elements of wondering

“When the Earth System goes from a previous state to a new state,” explains Anthony Barnosky of Stanford University and the Anthropocene Working Group, “what happens in the transition is a lot of bouncing back and forth between something resembling what’s going to be the new state, and what looks a little more like the old state—really wide fluctuations. That’s probably where we are right now.”

PP: Hello and welcome to Buckslip 2023. Happy to have you fluctuating with us still.

Scratching around our Earth System for inspiration to get words flowing awhile back, still thinking on ideas of wonder I wrote about last issue, I read this handy how-to guide by a psychology professor on “how to revive your sense of wonder”. It explained, with wonder:

Wonder moves someone to seek out explanations – especially about the patterns of cause and effect that underlie phenomena. It is also different from awe, which can occur as a more passive state of amazement. Wonder involves active thought and engagement. It invokes conjectures about ‘how’ and ‘why’. It might even launch speculations about different possible worlds. Wonder motivates targeted explorations and discoveries. In its most mature forms – in adults who have flourished as lifelong wonderers – wonder promotes sustained excavation of the rich causal architectures of the world. It helps us to appreciate everything around us more fully. We come to see a more richly textured and dynamic reality. For example, through wondering and learning about how and why songbirds sing, how the first flowers break through frozen ground, and how animals hibernate, we come to see and experience the first days of spring in more immersive and rewarding ways. Each instance of wondering in turn launches a branching network of new instances and opens a door to the potentially endless joy of successive discoveries.

Fuck yeah, I thought, as the article went on to describe "sophisticated elements of wondering”. At the time I was probably looking out of a window on the Atlantic coast, watching plovers scrabble around in the tidal zone, seals competing for the best rock to banana-bask on, my partner out on the rocks with her feet in the tide pools, poking at crabs. Endless joy out there.

But wonder can be seductive. It can be hard to demand too much of the things we want to believe.

Think of this opinion, delivered to Nature with a resigned mix of anger and sadness, from a group of scientists tired of the wonder-grifters like Peter Wohlleben who continue to oversell the idea of mycorrhizal networks, or the wood-wide web, beyond the very real truths of the underlying concepts that the science is only just beginning to show.

Their review of the science shows, they say, not that “effects do not occur, but that we must be aware that they have not been shown definitively to occur in the field.”

“Too few forests have been mapped,” they write.

That’s a hard thing to hold wonder in. But it’s science — it does not say that the effects of these networks in forests do not exist. It simply says, we do not know that they do. It outlines a multitude of experiments that might tell us better.

And with their pencils whittled sharp: “In line with previous calls, we believe that the anthropomorphism currently present in some science communication on CMN function in forests should be reconsidered.”

They go on to suggest a vast array of ways in which the science can be improved. Experiments to conduct that might prove this out, before we get ahead of ourselves.

Probably when you read about this paper in the more mainstream media, you’ll read “the mushroom networks were a scam”, or “the wood-wide web is untangled”, or whatever.

But that’s not what they say. For our purposes today, focus in on their last paragraph:

“Let us devise new experiments, demand better evidence, think critically about alternative explanations for results and become more selective with the claims we disseminate. If not, we risk turning the wood-wide web into a fantasy beneath our feet.”

In other words:

We do not fix the world with a sense of wonder alone. Wonder is a starting point and the world is full of it. Use it, don’t stop at it. We have to get to work.

Some other points either related to this or not:

- “Who will now undertake to say that a plant is not sensible? If you go into the fields, you will tread upon a multitude of flowers that know better than you do which way the wind blows, what o’clock it is, and what is to be thought about the weather.”

- Scientists say, if we deployed a fleet of 125 high-altitude air-to-air refuelling tankers somewhere around Anchorage and Patagonia, “whereby high-flying jets would spray microscopic aerosol particles into the atmosphere at latitudes of 60 degrees north and south—roughly Anchorage and the southern tip of Patagonia”, maybe we could refreeze the poles. “Refreezing Earth’s poles feasible and cheap”, is the headline.

- In January, Abu Dhabi sponsored a meeting of the Arctic Circle forum, to discuss what those facing glacier-melt in the Himalayas and the other great ranges of Central Asia could learn from Arctic communities already facing it.

- If you plant a carbon offset forest, the thing is sometimes forests burn.

- Ship noise is not good for the libido of crabs. And hot sauce doesn’t keep dolphins away from nets.

- “As plague travels, so does ritual. Traditional hunters are attuned to sentinel marmots, those lookouts who stand erect at the portal of the burrow and warn the colony inside of a predator’s approach. Their behavior is diagnostic. Sluggish or unsteady marmots suggest that the whole colony might be diseased and should be avoided. According to oral tradition, the sentinel marmot of a sickened colony will set out on a journey to find medicinal plants. Such marmots, observed on their own, far from any burrow, are likewise not to be hunted.”

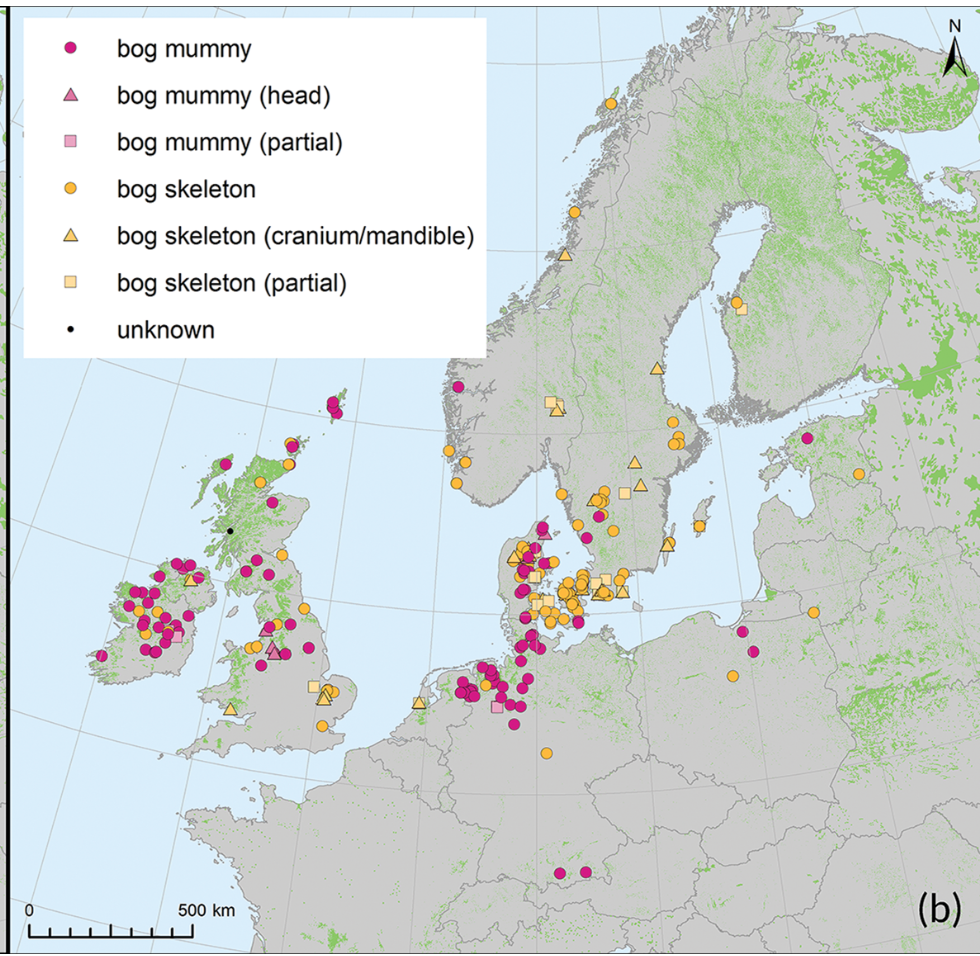

- This is a very useful database of all of northern Europe’s known bog bodies, from 9000BC to AD1900. Here is a map of them:

- And so Fred la marmotte died a day early and no groundhog shadow was seen. We wonder what will become of the rest of spring.

Cheadle, Alberta, the home of the new Cheeto finger statue. 😯 pic.twitter.com/rJTu87Wex1

— Made In Canada (@MadelnCanada) October 4, 2022

02. A thing that we made that you can eventually buy

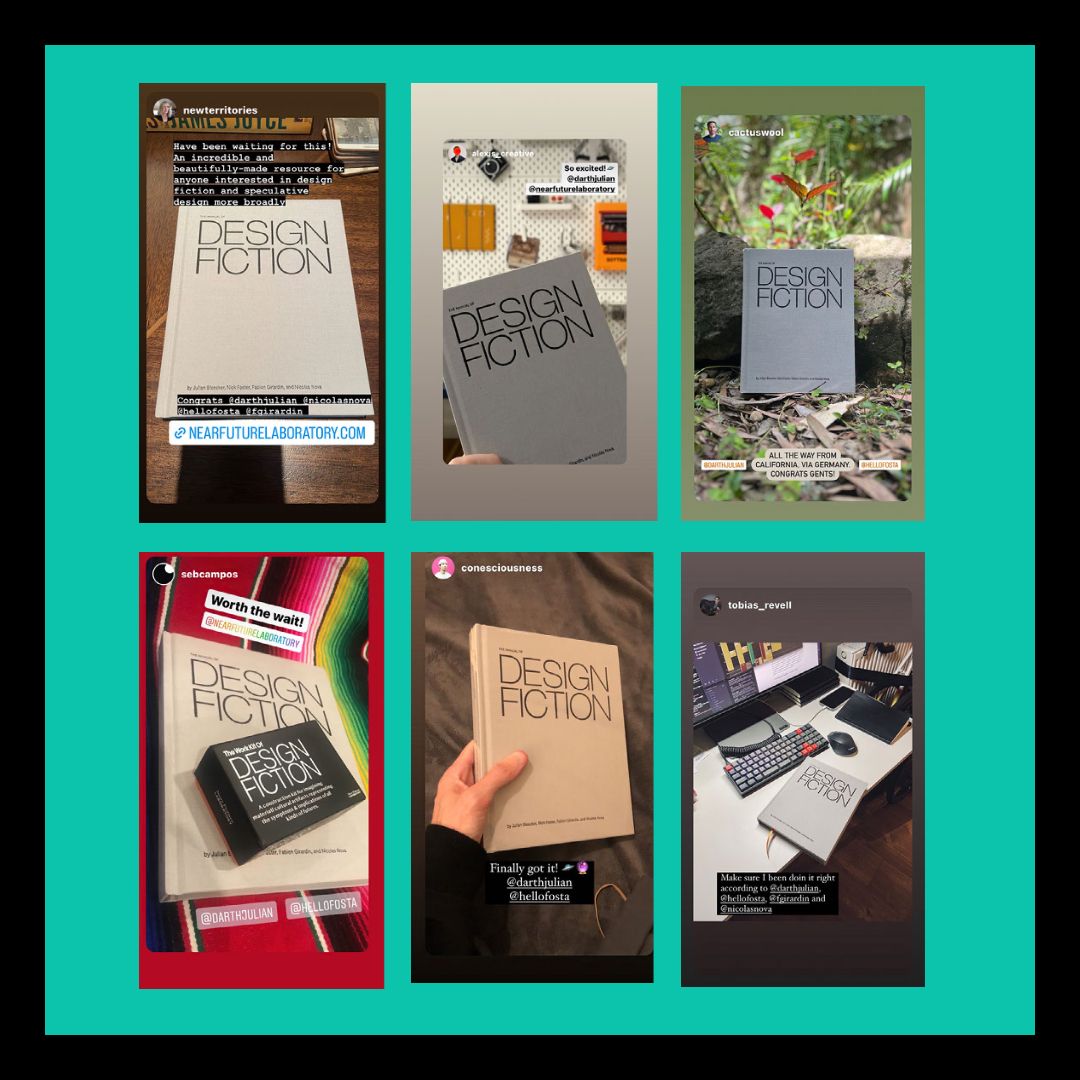

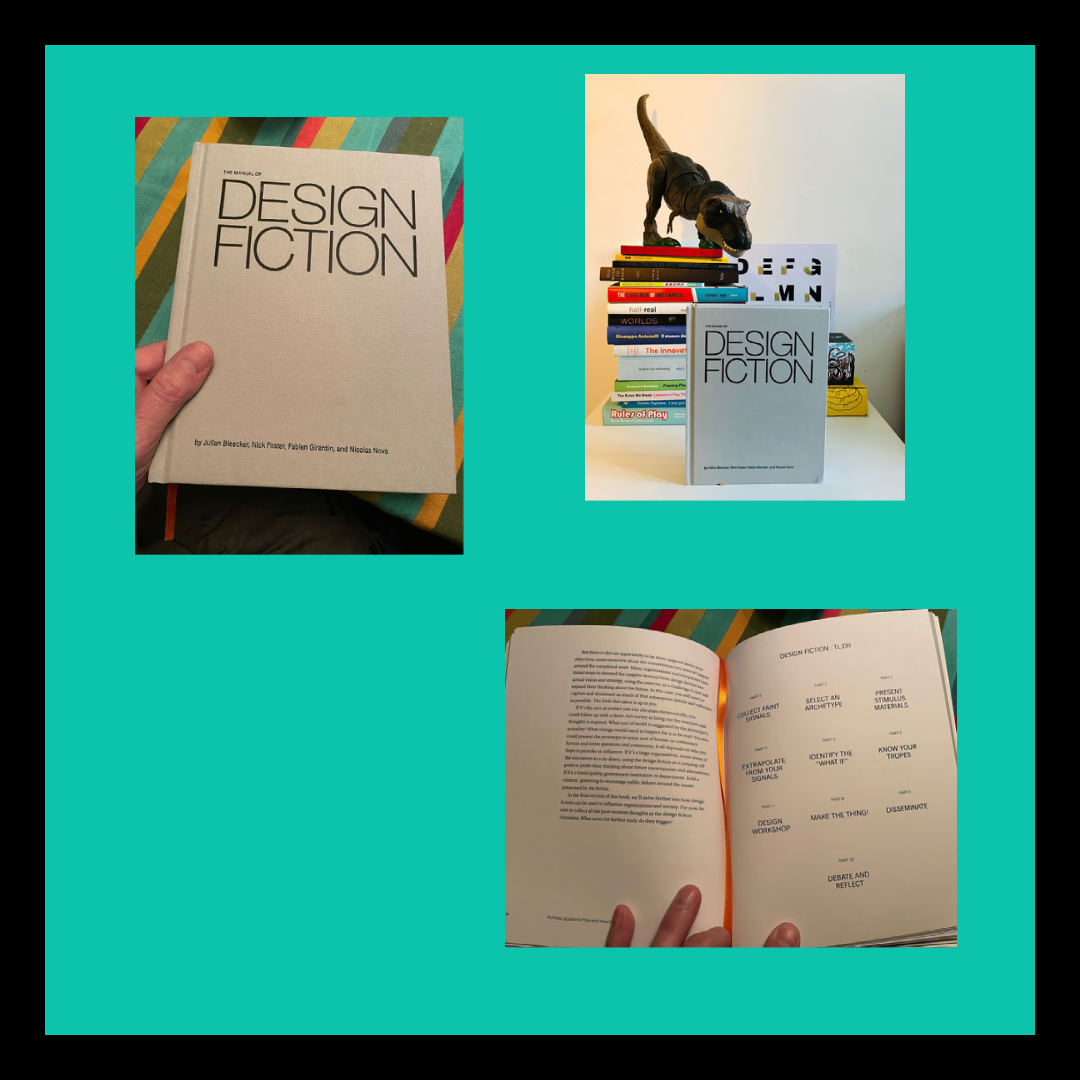

So we (Chris F and Patrick as No Media Co and also Chris Lange in the big design chair) spent many years working on The Manual of Design Fiction with our friends and collaborators at the Near Future Laboratory. Because we didn’t send you an email either before, during, or after its launch, we didn’t tell you it was available until, well… it was already sold out. (Most all of it through pre-orders, in less than a couple of weeks of its coming off press.) We were honestly surprised by how quickly that happened, but damn proud of it too. Here’s us on the Near Future Lab podcast reflecting happily on the process.

The good news is we’re currently making the final tweaks to the Manual’s second edition, before it goes to print later this week. So if you missed it (and let’s face it, you probably did), it’s not too late. There’s a waitlist to sign up for the second edition over at the NFL site. Or you could just let us know if you’re interested in a copy and we’ll tell you ourselves.

As Anab Jain says of it, in her kind blurb:

“this is a book about an approach, a philosophy, a mindset. And a crucial one at that; one that will not limit us to tools we already use to address familiar problems, but rather an approach that opens up the ways in which we can address uncertainty and traverse new possibilities.”

It’s been pretty cool to see the enthusiasm a book you put so much care into receives as it arrives in its new homes, and a new community of readers emerges. Here’s some shots of that happening.

If you managed to get hold of a copy, we’d love to know what you think. Otherwise we promise we’ll let you know when that fresh paperback has made it back from Istanbul.

In extracurricular news, earlier this month we had a hand in the February instalment of Trampoline Hall, the long-running Toronto-based barroom lecture series founded by Sheila Heti—with Chris curating and Patrick delivering one of the lectures. There’s a kicker to the lectures, of course, which is that lecturers must speak on a topic at which they are not professionally expert. For Patrick, that meant “Google Street View as time machine”. Amy Blaxland spoke about “Tragedy as personal fetish. And Buckslip friend Mike Takasaki discoursed on the hot topic of “Hot Dog vs. Hotdog”, and one man’s descent into linguistic and tubular-meat pedantry.

03. Hard times in Walmart Land

“Nothing, Forever,” the infinitely-generating AI version of Seinfeld that tens of thousands of people were watching has been banned for 14 days from Twitch after Larry Feinberg—a clone of Jerry Seinfeld—made transphobic statements during a standup bit late Sunday night.

Consider that little quote a melancholy reality palate cleanser as you watch this next video — one that’s been lingering with us for months now.

This video of Walmart's chief marketing officer on a stage in Roblox talking about its new "Walmart Land" experience is one of the saddest videos ever created. pic.twitter.com/HtIIToShKs

— Zack Zwiezen (@ZwiezenZ) September 26, 2022

Just the utter sadness of it, sure — a throwback to some of the weirder moments of the Second Life era, when government arts funders were encouraging us to pivot all of our creative projects onto that platform, and also holding funding meetings in similar empty voids. But there’s something deeper in that bleak void, in that corporate drive to find the “next generation of shoppers,” boardrooms full of executives sure there’s a market there because they’ve been told that one day, some day, the children of Roblox will find their affinity with Walmart. We can make them love us (and not unionize) if they know we love their blox.

“How are we driving relevance in cultural conversation? How are we developing community and engagement? How are we moving the needle from a brand favorability [standpoint] with younger audiences?” White said. “That’s what we’re trying to accomplish here.“

In our left hand: McKinsey for Kids. In our right: Business Dudes Need to Stop Talking Like This.

More entertaining, Adobe’s concept video for Acrobat’s metaverse version. Dig that floating window. Mint us an NFT of it?

Instead, let’s spend some time with the odd soul that is Tom Persky, last keeper of the floppy disk flame. Maybe the last person on earth with a warehouse full of magnetic media for sale. Our kind of business strategy: “There is a growing market share for the last man standing in the business, and that man is me.”

As we drift forward into this robloxic future, hold onto the knowledge that it will remain as fragile and dependent on the esoteric whims of human endeavour and stubbornness as it always has. For instance: the protocol that keeps the clocks of the world’s computers in sync—NTP—still relies on the vagaries of a few cranky old volunteers, and one retired engineer in particular, David Mills, the “benevolent dictator” of the protocol, born with glaucoma and now completely blind and unable to easily explain or examine code. Don’t lose sight of what motivates the truechimers and falsetickers of our core protocols. They’re what made this crazy place, and they ain’t easy to fix.

miyazaki of studio ghibli, upon seeing an artificial intelligence presentation- "i strongly feel that this is an insult to life itself". pic.twitter.com/UmOOWvsfjV

— Tofu (@TofuPixel) December 12, 2022

04. Speed run

- Ted Chiang, as he near-infallibly is, is so precise, wise, and unfearful in ChatGPT is a Blurry JPEG of the Web. Mostly it inspired us to think about Xerography again, so you’ll probably have to suffer through that in a future issue.

“The fact that Xerox photocopiers use a lossy compression format instead of a lossless one isn’t, in itself, a problem. The problem is that the photocopiers were degrading the image in a subtle way, in which the compression artifacts weren’t immediately recognizable. If the photocopier simply produced blurry printouts, everyone would know that they weren’t accurate reproductions of the originals. What led to problems was the fact that the photocopier was producing numbers that were readable but incorrect; it made the copies seem accurate when they weren’t.”

- An epic read that took years of work from friend of BS Sarah Souli in The Atavist, A Matter of Honor:

“Life in a diaspora can have the dull ache of a phantom limb. In the Istanbul neighborhood of Zeytinburnu, in August 2021, the pain was acute. More than 2,000 miles away, the Taliban was starting to take back control of Afghanistan; within days the country would fall to an old regime made new. The events had plunged Zeytinburnu, an enclave of tens of thousands of Afghans displaced from their home country by war, poverty, and other ills, into a state of collective fear and mourning. The context seemed to render my investigation, now dragging into its third year, futile. What did three dead women matter when a whole nation was having its heart ripped out?”

To prove that a statement is undecidable, mathematicians typically show that it’s equivalent to another question that’s already known to be undecidable. As a result, if this tiling problem turns out to be undecidable as well, it can serve as one more tool for demonstrating undecidability in other contexts — contexts well beyond questions about how to tile spaces.

In the meantime, though, Greenfeld and Tao’s result serves as a warning of sorts. “Mathematicians like beautiful, clean statements,” Iosevich said. “But don’t believe everything you hear. … Unfortunately, it’s not a fact that all interesting statements in mathematics need to be pretty, and that they need to work out the way we want them to.”

05. This is in part a newsletter about shorebirds

A+ shorebird content: At fall migration time, Passamaquoddy Bay was once abundant with millions of red-necked phalaropes. Willy Blackmore gets to wondering, where did they all disappear to?

In High Country News, B. ‘Toastie’ Oaster on the drama and timeless importance of eeling in the Pacific Northwest. The Pacific lamprey’s use (and difference to our bad-news other coast lampreys) is understudied outside of tribal fisheries. Their significance is passed down, Oaster writes, in myths that “aren’t just stories; they’re stratified memories.”

“Lamprey have lived on Earth for 450 million years. To them, dinosaurs were a passing fad, and the North American continent is a fairly recent development… They’re the target of misplaced disdain, in part because they’re easily confused with sea lamprey, an Atlantic species that caused ecological havoc in the Great Lakes after a 19th century shipping canal allowed them to invade. Pacific lamprey are a different species, in a different ecosystem; they belong here, just like the people they sustain.”

In Grist, a look at the possibility of learning something about climate change from 18th-century whaling logs. “One of the most important pillars in understanding how events are, or are not, changing is observations,” says the scientist here, and maybe that’s what Ahab was saying too.

So let’s closely observe the Narwhal too, now, where they are and where they aren’t. There’s something in there worth understanding.

In Bettles, Alaska, as Bree Kessler learned by living there, and observing, there’s a lot worth understanding in how locals plan around food procurement and nutrition through sharing, careful seasonal stocking, and communal living. One thing that makes those traditional ways less necessary though? Amazon Prime.

Cleanser: A Master Perfumer’s Reflections on Patchouli and Vetiver.

Patchouli was the fragrance of our generation. Smelling like the earth, undergrowth, youth, and freedom, it connected us to the imaginary world born of 19th-century Romanticism, when the word “patchouli” first appeared. In a commentary on Baudelaire, André Guyaux noted that the poet “didn’t need to go looking far for a little jar of heliotrope or tuberose, a bag of peau d’Espagne or a cashmere shawl redolent of patchouli cast on a sofa” to find himself spirited away. We, too, wanted an earthly paradise that wasn’t artificial. Perfumes that contained such elements in profusion were Patchouli (Réminiscence, 1970), Aromatics Elixir (Clinique, 1971), and Gentlemen (Givenchy, 1974). Fifty years have passed since then, and patchouli no longer has the same currency. Our sense of smell is different now, and our memory has other points of reference: wax, cigars, and pu-erh, the tea of emperors.

cant believe nyc is gonna pay mckinsey millions of dollars to invent the dumpster https://t.co/FS89B0GVUr

— matt (@questionableway) October 3, 2022

06. I feel I am about to invent Surrealism 2

- Patricia Lockwood, at her best, writing of her husband’s almost-exploded intestines. As in the second half of her book, she captures so perfectly that disorientation of what happens when bodies don’t behave as we expect, and when science too feels like it can only shrug.

I felt my phantom hands shuffling for cards and papers, the twist of the suitcases in my shoulders as Dr Khalid told me that I should play sports. ‘This is sports, Dr K.,’ I thought, seeing again the red field where figures were wrestled down. I could not be here because I was trying to be there: the body simply goes away when you are trying so intensely to project yourself into someone else, blinking in and out, in pain and on morphine, on the verge of being wheeled back. ‘All of it is so unreal and so convergent,’ I wrote on the hotel stationery, ‘that I feel I am about to invent Surrealism 2.’

- Inside the history of the great, and mysterious Japanese band Les Rallizes Dénudes who, when you write something about how they exemplify “the sonic extremes of rock and the ways that online communities can nurture and amplify even the most obscure corners of global culture”, you make them sound much more boring than they actually ever were.

- David Toop at The Wire, with “a short story of longform music”:

The durational marathons that have no attachment to an observance, other than music itself, could be thought of, at the very least, as a resistance to drudgery, a pushing back against the arbitrary temporal limits set by technologies, a questioning of spurious theories about human attention span, yet also a feeling of grief that so many of these intricate, deeply established rites have been disassembled in a matter of moments. The shards lie on the ground around us all, dispersed and abject as all the other entities of the world, things underfoot.

- Anab Jain, again!, with an “emergent lexicon for critical activism” that surveys a lot of the work and thinking that’s been providing useful tethers for us, too, of late:

“A world of mutual aid, as such, is built on the sediments of our histories and presents; it is a world of precarious flourishing, where unexpected alliances emerge from the debris of what has passed.”

- In Orion, Kaitlin Smith on eating acorns (balanophagy!) and learning from Octavia Butler. (And then play with this fun NY Times Interactive Octavia Butler thing as a chaser).

“May we cultivate the capacity to see a world—our world of seemingly endless complexity, beauty, and ugliness—in an acorn as Butler did, and then grind it into our most sacred nourishment.”

- Goddamit, rest in power Trugoy the Dove. For those of you who might ever need it, as their music finally arrives on the streamers, here’s A Guide to Getting into De La Soul. In there’s all the joy and wonder you need to find right this moment.