The Thing

Let’s not forget that in our horrendous confusion — in spite of it, because of it — we managed to do something amazing. We chose to go dormant. We changed almost everything in the world, almost overnight. This required a kind of collective action that, frankly, would have struck me as impossible five months ago. There are, of course, outliers, loudmouths and nihilists and malcontents. They will always exist. But enough people are not that. Enough of us have found enough reasons to change, and it has made an actual difference. We are in the middle of creating whatever the new world will be. We did it, and we are doing it, every day.

Meanwhile, I am still sitting here in my chrysalis, ravenous, sad, confused, feeling simultaneously changed and unchanged. Perhaps one of these afternoons, many months from now, I will be nibbling away at whatever happens to be in front of me, and it will turn out not to be more gummy bears but something else, the actual wall of my enclosure, and I will eat enough to make a hole, and then I will look out, with a whole new kind of eyes, to see what sort of world is waiting for me, and what I have become in it.

– Sam Anderson, The Truth About Cocoons

Yesterday I made it into the woods for the first time in months. In best Canadian style in the time of pandemic, this meant a pre-booked two-hour slot to heed the scheduled call of the regulated wild. From an outcrop on the Niagara escarpment, I sat and watched the turkey vultures loll along on the thermals, seemingly even less bothered about human presence than usual. Like Helen Macdonald paraphrases Iris Murdoch here, “when feeling anxious and resentful and caught up in your own concerns, you might look out of the window and see a hovering kestrel; stare at it — and then the world becomes all kestrel, just for a while.” It’s a peace you can pack up and carry home, for a little while, if you’re lucky enough to have a (rusting, A/C-broken, brakes-questionable, you-just-want-to-get-in-it-now-and-drive-it-all-the-way-around-the-Great-Lakes) car and can escape the packed downtown parks.

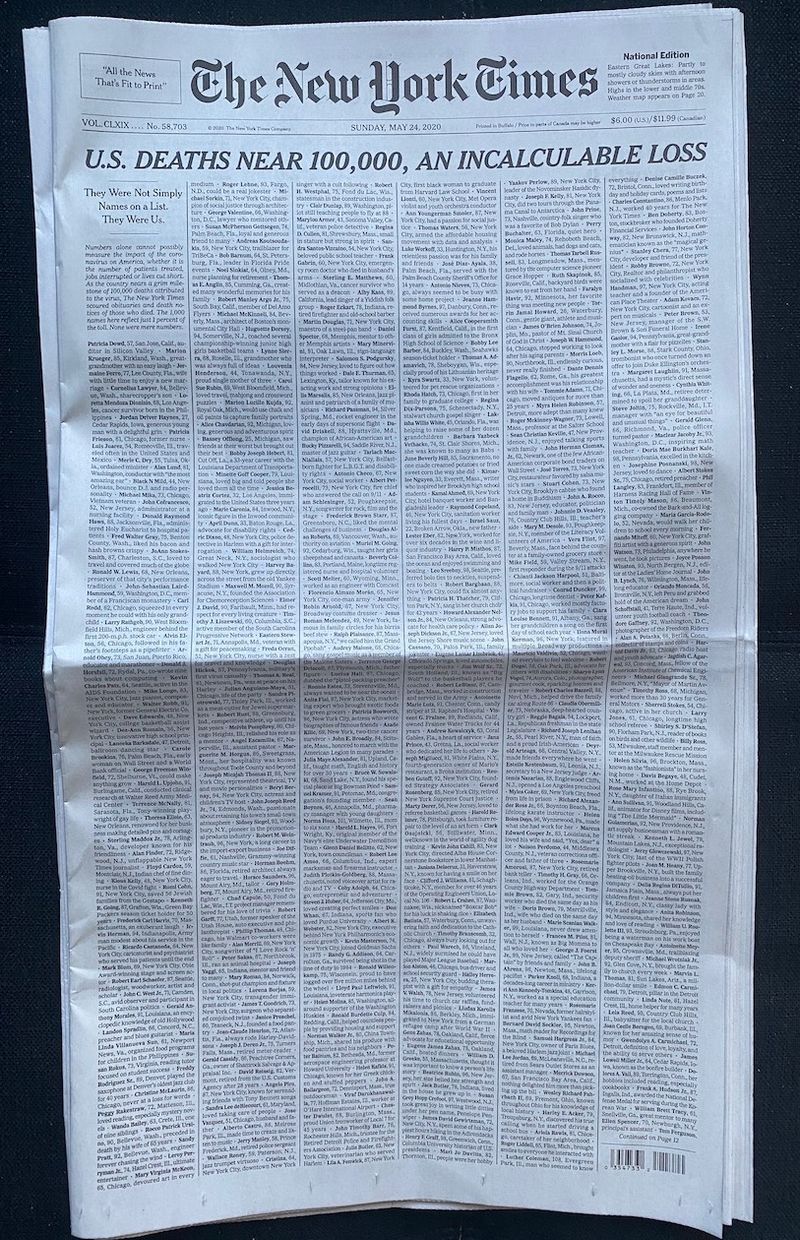

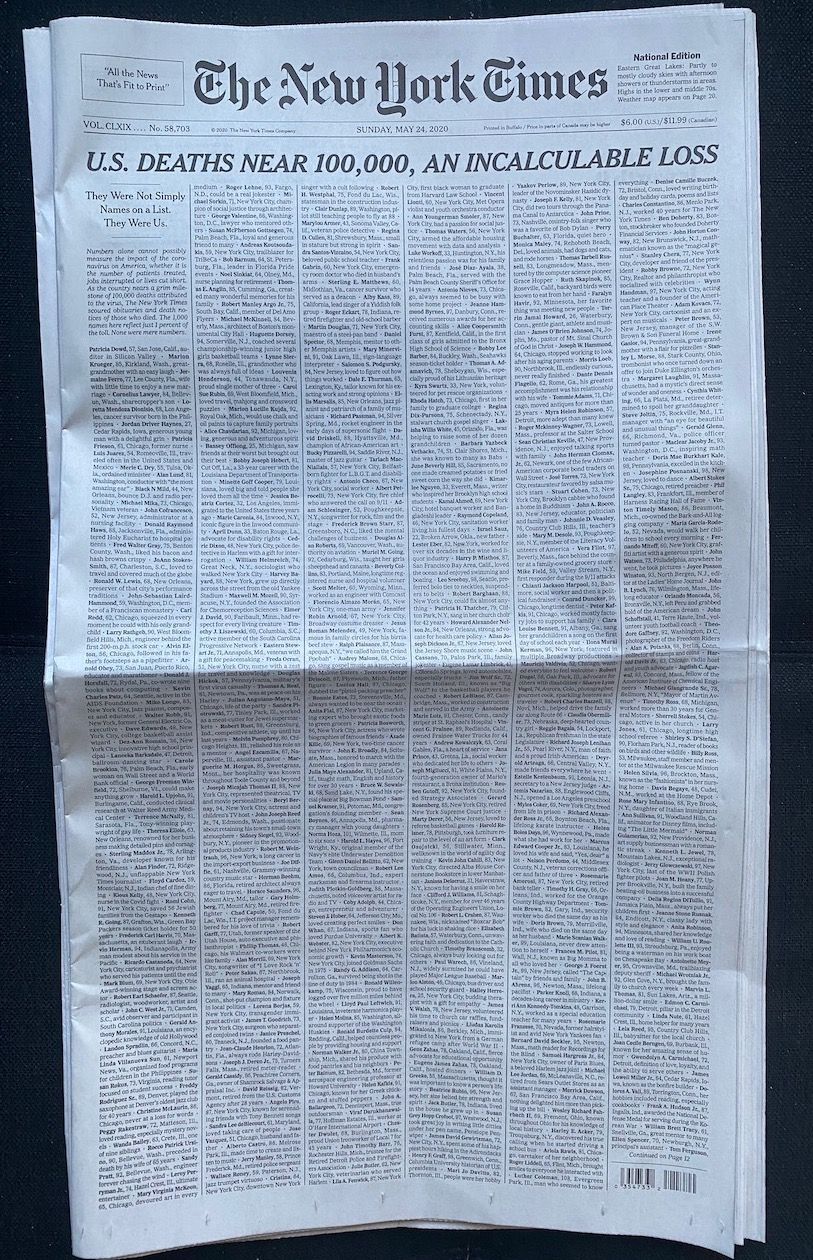

And then this morning, the New York Times arrives at my door, as it does every Sunday, and its cover is a black hole that dragged my placid kestrel/turkey vulture soul to the ground with a thud. I’d seen jpegs of it yesterday. Those didn’t prepare me. The thing itself, my god, this physical thing, a multi-page list that is simply the names of 1,000 lost, one percent of the American dead, and one small fact about each of them: Enjoyed the mandolin. Renegade nun. Loved his whole family. Knew how to make an entrance. Just running your finger over them, you fall into their worlds. Part of me wants to talk about how it’s just great design, and it is, historically so, a single page of print that you know will be in the history lessons half a century from now. But it’s something else as well. It’s a thing that’s sitting now on my coffee table, dragging me in, making it hard to stay a kestrel.

In fact that’s three stories I’ve just linked from the same edition of the same newspaper, just for a moment slipping out of the awful day-to-day reporting of this thing and the awful people making it worse, to try to create an object that reports what it is to live this. That feels like something worth noting, for all the justifiable objections about that particular gray lady that I share on most days.

We continue to argue about what we want to be from here. An exercise — first, force yourself to look at how the McKinsey suits are arguing for a return to the old normal in the new. It’s a morass of mixed metaphors about nerves and muscles and bodies, and sandbars and oceans, a masterpiece of saying nothing and arguing for little more than the continuation of the machine, without questioning need or considering the human. A manual for how to perform what we were. This is what the boardroom Zoom conversations look like now, I have no doubt. And I’m sorry for telling you to read it. But then, chase it with these two important, necessary essays from Astra Taylor and Marilynne Robinson, which collectively map the layout of the prison yard we realise we’ve been standing in for much longer than these last few months, as we stare at the hole in the fence wondering whether to make a run for it. Robinson thinks she’s writing about America, but she’s writing bigger than that. What I got in the space between those is a momentary certainty that it’s not us who are lost in this — it’s them. They too do not know what they are becoming, inside of this cocoon.

So, as I turn away from my tabs and back towards this endless Twitch of 1980s computer shows, I’m thinking of one other great pandemic essay I read this week, Gabrielle Bellot on E.M. Forster’s The Machine Stops. Which, sure, predicted social distancing, etc, but that’s not Bellot’s real point. She’s working her way through the reopening, through the suffering, and as I sit simultaneously kestrel-calm and terrified that we’re trying to get back to before, too quickly, this gets to the heart of it:

“The machines keep going, allowing those of us who are luckiest to have tech in the first place to keep their livelihoods without venturing out too far into the unsafe—but distance is as much a luxury and a life-saver as it can be something that lethally weighs on us, and I just want to be able to bear that weight a bit longer. I want to keep trying to believe in my loved ones surviving, because that is the only thing that makes the weight a bit more bearable.”

I hope you’re finding your own weight bearable this week.

– Patrick

Things

Kate Wagner of McMansion Hell catalogues the sort of bullshit concept art for fictional objects masquerading as will-actually-be-made design we’re seeing plenty of during the pandemic — coronagrifting, she suggests, designed to get a few clicks for/from Dezeen — but which, for better and for worse, has always been part of the industry hustle. Just that it used to be genuinely fun.

Much more helpful on the design front is Nicholas de Monchaux’s historical deep dive into “The Spaces That Make Cities Fairer and More Resilient”:

Much has already been written about how this pandemic provides an opportunity to remake, or redesign cities. But such statements mostly reveal our recent, pharmaceutical-era amnesia about the inextricable history of disease and urban life. The fact that the same forces that bring us together to share and create also create the possibility of contagion is a design problem as old as cities themselves. And some of our best and most effective public spaces are the result.

As activist-architect Michael Sorkin once wrote, “Politics programs our architecture.” Sadly, Sorkin’s was another of the names on the Times list of those Americans lost to Coronavirus (“Champion of social justice through architecture”). Which had us revisiting his wonderful Two Hundred Fifty Things an Architect Should Know from a couple years back, and we can’t think of a single thing to quibble with.

74. How the pyramids were built.

75. Why.

76. The pleasures of the suburbs.

77. The horrors.

78. The quality of light passing through ice.

79. The meaninglessness of borders.

80. The reasons for their tenacity.

81. The creativity of the ecotone.

82. The need for freaks.

83. Accidents must happen.

Last weekend the football came back. Sort of. The German Bundesliga kicked off again in what felt like a strange reenactment of a sport its players were attempting to reconstruct from oral history. Sure, the elements of what make it football were there — a round ball, 90 minutes, 22 people kicking the ball and each other. But it was also not the sport at all. It was a performance of it an empty stadium, where every little slide, every shuffle, every flicked blade of grass carried through the mics, sometimes it seemed even the sound of a substitute muttering from behind his mask on the bench. The great football writer Jonathan Wilson called it “football’s Dogme 95 moment”, which feels sort of right. Maybe football’s Dogville, to be specific. The vast emptiness of it all had the paradoxical effect of amplifying solitude, somehow? Not what we’d hoped for, but probably what sport’s going to be from here. Two solutions mooted to mitigate: pump in some form of smart EA Sports-style crowd noise, or follow South Korea’s lead and fill the stands with sex dolls.

In a time of ridiculous and depressing numbers of layoffs and shutdowns, it’s nice to see new media outlets launch. Rest of World seems a promising new technology outlet, with a focus, as its name suggests, on the lived experience of technology in the countries and territories most of the other mastheads ignore, except when that “rest of world” phrase pops up “rendered on user growth charts as blank space, virgin territory for the hockey stick to scale up into,” as Mattathias Schwartz writes in this well-considered piece about what Valley conceptions of scale mean to, say, actual people in Myanmar on either side of a rising tide lifting them inexorably towards genocide:

“Staffing up in a market as small as Myanmar or tailoring Facebook’s architecture to take local conditions into account were not viable options. Such measures would have violated the notion that technology is neutral with respect to geography, because all users are the same. Silicon Valley, in other words, had convinced itself that it was delivering products with the universal homogeneity of Coca-Cola but even more profitability, because they didn’t require any in-country trucks, syrup factories, aquifers, or bottling plants. But they were wrong. Internet platforms are not at all like Coca-Cola. In fact, they provide an entirely new way of engaging with the world, a system for finding and sharing refracted bits of consciousness that mutate upon contact with each market. And despite the neocolonial assumption that high-speed internet access could be only a civilizing force, in many cases it proved to be an accelerant for the worst impulses coursing through a society”

Speaking of scale: Facebook bought Giphy. All those cute little reacts we were sharing in even our private message threads? Yeah, those were beacons. And yeah, they own that data now.

have been a culture editor for a year now and yet the culture is still full of errors

— Ari M. Brostoff (@AriBrostoff) May 15, 2020

From Undark, a fascinating and in-depth report on the little-noticed-outside explosion in crystal meth production and use in Afghanistan, driven by the abundance of the ephedra shrub throughout the country.

We’re pretty fascinated by Scite, a service (and browser plug-in) that maps and evaluates scientific papers by threading them with those that have either supported or critiqued them (rather than simply saying, in a neutral sense, whether or not they were cited).

We didn’t think we’d have much, if anything, to say on the whole Alison Roman/Chrissy Teigen/Marie Kondo thing, being too exhausted to look at it much more deeply than just the iso-frenzied internet desperately needing to cancel somebody for sustenance. But we were also sure that there was a substantive argument about culinary appropriation being put forward by many of the critics that, if somebody could piece it together in a useful way, would elevate the whole thing out of celebrity spat and somewhere towards useful discourse? So step this way, BS favourite Navneet Alang, with an Eater essay that’s rightly being widely celebrated for doing just that, and doing it remarkably well as he asks: “Who gets to use the global pantry or introduce ‘new’ international ingredients to a Western audience? And behind that is an even more uncomfortable query: Can the aspiration that has become central to the culinary arts ever not be white?” For anybody studying this question in the years ahead, it feels like Nav’s maybe just written the foundational text.

Dumb good vaguely propagandistic podcasts about spies for quarantine comfort food when you’ve run out of le Carré novels: Patrick Radden Keefe investigating whether the Scorpions song Wind of Change was a CIA plant, and Foreign Policy’s I Spy, in which character actress Margo Martindale introduces various first person declassified spy reminiscences.

Alright, that's it. No more Elon Musk for you guys. You lost your Elon Musk privileges. I'm taking him away for a little while until you learn to behave.

— willy (@willystaley) May 5, 2020

“Technology Melds Minds With Machines, and Raises Concerns.”

As we fetishize AI and machine learning, it’s enlightening to look at the mundane ways the machine learning algorithms that run our global just-in-time supply chain have been tripped up by something very basic that’s happened during lockdown, leading to condiment shortages in India and broken fraud detection on our credit cards with all the weird shit we’re buying in our boredom: “Machine-learning models trained on normal human behaviour are now finding that normal has changed, and some are no longer working as they should.”

Related: at Aeon, historian Amanda Rees looks at the tensions inherent in the development of “cliodynamics”, a “science of history” that attempts to find ways to tell and use our past through numbers rather than narratives, to turn historical models into big-data-driven predictive tools.

If you wanted to know anything at all about QAnon and the current state-of-the-art in conspiracy theory, Adrienne LaFrance’s “The Prophecies of Q” in the latest Atlantic will probably have you covered (in tin foil).

Just a normal Beijing night at a normal bar in a normal city: a security officer with a shirt that flashes like a police siren, taking photographs of all the patrons every 20 minutes. pic.twitter.com/Tiy7M1Wekh

— Krish Raghav (@krishraghav) May 22, 2020

Badly want to play with: Out for Delivery, a 42 minute, 360-degree interactive video about delivery workers in Beijing, shot on the day that Wuhan was shut down.

Look, The Secret Lives of Fungi is probably not Hua Hsu’s best work for The New Yorker — it pretty much reads like he just wanted to write a long, elegant list of facts about mushrooms and people who care about them, without much in the way of additional insight or magic. But look, a long, elegant list of facts about mushrooms and people who care about them is absolutely something that we will celebrate. Thanks, Hua Hsu.

Rest in peace Lynn Shelton, whose films were always just low-key great in ways it was always really difficult to explain to somebody else. All the best bits of mumblecore, except shot through the lens of somebody who cared about people. Who knew how to listen to the silences in even the most frantic of rambles. Fuck.

Robin Sloan takes the beautiful looping decay of William Basinski’s Disintegration Loops – a strange post 9/11 masterwork we’ve probably posted about on here before sometime – and feeds the fragments at its heart it through both neural networks and friend networks to create something new, something full of potential, stronger in those broken places.

This past Friday marked the 10th anniversary since the passing of Toronto artist, impresario, community builder, and all-around queer alt-culture hero Will Munro, at only 35 years old from glioblastoma. So much of what still seems radical or inspiring or even just fun about Toronto —especially in the rapidly gentrifying west-end pocket where we live — Will helped create a space for. We never got to know Will personally, but our hearts go out to the many friends of ours who did. Poring over this moving but also hilarious collection of reminisces and ‘love letters’ dedicated to Will, there is a sense in which his life reads as one big call to action.