The Thing

A couple of months back, a review copy of the 2020 edition of The Best American Travel Writing showed up in my mailbox. What a ridiculous thing, I thought, from somewhere in the depths of the unproductive funk I’d been camped out in over recent months. We weren’t yet back under a stay-at-home order here in Toronto, but you knew it was coming. Last year, of course, was a year of journeys not taken. The idea of moving as I normally would through the world seemed absurd now. Even the actual reporting and research trips I had planned seemed like abstractions from a different life. The idea of some time in the future when a travel writing anthology wouldn’t feel entirely wrong just didn’t sit right at all.

Back in April, I received a letter from the writer Barry Lopez, typewritten as they always were. This would sadly be the last in a treasured conversation held at the pace of a letter or two a year in the time since we met at his Oregon home (since taken by wildfire) for a conversation I’ve linked here more than once before. In this last letter, he wrote how both the coronavirus and the rise of nationalism had “a way of making lyrical rumination seem self-indulgent” as he considered his own work ahead. But he wrote too with hope, as always, of how international awareness will be essential to rebuilding on the other side of all this. A focus on the human, he wrote, was what was needed. Since he died on Christmas Day, I’ve been reading those lines over and over, through weeks where the meme warriors stormed the castle and reality once again went to war with itself, wondering how to journey again towards those more human stories. Wishing once more to sit on his porch and ask him something about what difference a person can make by going out and listening to the stories of others at the edges.

As I scanned the contents of the anthology, I remembered how glad I always am to find myself seeing that world, out of reach, through writers I trust. From Kyle Chayka’s Iceland to Ben Mauk’s Kazakhstan via Yiyun Li’s remote Finnish islands, I saw that urgency of looking at the world, always, through fresh eyes. A world still alive, still teeming with weirdness and broken things and beautiful things too. Good people and evil ones. Just with a virus teeming around all of them. Not on hold. Not on pause. Just living.

In his intro to the anthology, Robert Macfarlane (another BS staple) writes that lockdown “has triggered a greed for what cannot now be done as we restlessly pace our cages.” With our bodies anchored, he writes, we journey in imagination instead. And sure, I do my fair share of that still. Travelling via a map of the world’s forest sounds, say. Hanging out on the Mariana Islands for a while, listening to fruit doves and fantails. Recording passages of Robin Wall Kimmerer writing about moss and peat bogs I’ll never visit, as much for my own comfort as that of those I send them to. Retreading old roads of my own, as when good friend of the email Fabien Girardin loaded my reporting from Tajikistan a couple of years ago into his nifty Proximo app, where you (and I!) can follow along through faraway valleys I miss deeply.

I’d argue, though, that in some ways we’ve now moved beyond all of that. We’ve figured out new ways to live outside of our cages. We’re adapting. Sure, we had the anthropause as we all quieted down. Yes, the birds have changed their songs. Out here on the main street in my neighbourhood, an empty restaurant space is now a ghost kitchen selling, at last count, 17 different “concepts” on demand. From Monsieur Egg (bonjour, Monsieur Egg!) to Sōōp. Same chicken, different sauce, depending which corner of your delivery app you find it from. The strip club over the road is now a ghost vendor of chicken wings. Reddit went to war with the stock market. I waved over FaceTime to loved ones at a New Years party on the other side of the world, in a city where they can still have those—a privilege they earned through their own brutal lockdown. Air Force One took off on January 20, perfectly timed for the wheels to leave the tarmac as the last lines of Sinatra’s My Way echoed through the PA, shutting up the CNN anchors for just a moment.

The ground that plane left behind is different. We learn new ways to walk on it. Not stopped. Not imagining. From my lockdown to yours, I hope you’re finding good steps forward.

– Patrick

ps. If you fancy a soundtrack for this issue’s reading other than forest sounds, I made another mix, meant to sound a little like finding a warm corner at the end of a cold January.

Things

Alexis Wright on the “inward migration” of Indigenous Australians over the centuries to the one place where sovereignty still holds, and the critical work of imagination and listening that needs to be done in that place.

“This inward migration can be described as being locked in a prison of the mind. It can also be described as retreating to the dwelling place of stories: a return to country, going home to where the stories of our culture are kept in the mind—for the mind that knows how to read country. The inward migration is most often a solitary journey, a turning away from the bombarding speed of reality hitting your very sense of being and destroying your soul. Returning to the place of country held in the mind is a way of figuring out how to deal with the powerlessness we sometimes feel from having to continually hold back the end-of-the-world times and confront ongoing realities. It’s where we go to slowly pick things apart, to reimagine our world in new ways, and sometimes we come out the other side with a map of how to make some sense of our world.”

In Document, Caroline Busta scratches at an itch that’s been getting more noticeable for us for a while now. “With digital platforms transforming legacy countercultural activity into profitable, high-engagement content, being countercultural no longer means being counter-hegemonic,” she writes. “What logic could possibly be upended by punks, goths, gabbers, or neo-pagans when the internet, a massively lucrative space of capitalization, profits off the personal expression and political conflict of its users?” To us, this is a different and more useful question than whether cancel culture is enforcing conformist points of blah blah blah. Where and how are people allowed to be different, and what are they doing there? That’s more interesting. For help, Busta turns as we often do to Joshua Citarella’s work, which traces the underlying phenomena better than most anything else, for some form of sensemaking. This sentence stood out in this very Gamestop sort of week: “There is less focus on battling current leaders and more interest in divining counter-futures. Instead of attempting to dismantle the master’s house using the master’s tools, it’s more something like: Let’s pool crypto to book the master’s Airbnb and use the tools we find there to forge a forest utopia that the master could never survive.”

Cf. Max Read in Bookforum, back in September, in his appropriately frenzied review of Richard Seymour’s The Twittering Machine, pushing back against the standard techno-determinist view of us as zombie-like passive slaves to platforms. There are more direct, more human drives at work he (and Seymour) argue. We’re human, and humans don’t need platforms to know how to suck:

“Seymour’s book suggests something worse about us, their Twitter and Facebook interlocutors: That we want to waste our time. That, however much we might complain, we find satisfaction in endless, circular argument. That we get some kind of fulfillment from tedious debates about “free speech” and “cancel culture.” That we seek oblivion in discourse. In the machine-flow atemporality of social media, this seems like no great crime. If time is an infinite resource, why not spend a few decades of it with a couple New York Times op-ed columnists, rebuilding all of Western thought from first principles?”

Once Spotify thinks you like smooth jazz, you're fucked

— Adora 2000 (@Adora2000) January 13, 2021

Dare you to read Sam Anderson’s gentle, loving extinction tale, about the last two northern white rhinos on earth, without audibly gasping, cooing, stopping for sadness breaks, and thinking in great detail about morning scratchdowns. But as Anderson reaches to say something almost a little too maudlin about our capacity to love being the key to understanding extinction, it’s important to listen to the Kenyan caretaker who urges us not to anthropomorphise the creatures, rather to understand them as what they are, “contemporary beings” we are privileged to share our time here with. As Anderson comes to realise, "The girls do not exist for us. They are not symbols or oracles. They are not there to answer our existential questions or to help us save the world. They are something better and simpler. They are the girls.”

Two mundane stories, side by side, say something really nice that we can’t quite put our finger on. Systems are dumb, and simpler than you think, might be it. 1. Boeing 747s still get critical updates via floppy disks. 2. As Adobe Flash stops running, so do some railroads in China.

Me sowing: Haha fuck yeah!!! Yes!!

— Sen. Lemon Gogurt (R - MS) (@Ugarles) January 10, 2021

Me reaping: this is divisive and it's time to heal

Following the Capitol insurrection, Benjamen Walker responded on his Theory of Everything podcast in the only way that truly makes sense for that very particular and almost always wonderful creation—by revisiting a lecture given by Thomas Mann, in 1945, on collective guilt and shame. “There are not two Germanys, a good one and a bad one,” Mann wrote at the time, “but only one, whose best turned into evil through devilish cunning.“

From back in October, from before the great ramping-up, James Meek in the LRB on the conspiracist mind is still wonderful and useful reading, beginning its inquiry from a conversation held slightly too long with a pamphleteer in a park, journeying via David Icke back to Karl Popper and further. “This isn’t a conspiracy theory about the origin of conspiracy theories,” he writes. “It’s an observation that the interests of conspiracy theorists and the interests of the selfish end of the plutocracy have a way of aligning.” Meek does, though, make the mistake of trying to dismiss QAnon a little too eagerly – “It is interesting,” he writes, “but in the way hitting yourself in the face with a hammer is interesting: novel, painful and incredibly stupid.”

“In a way the saddest aspect of the epidemic of conspiracism is not the delusions about conspiracy but the delusions about what it is to learn. As Muirhead and Rosenblum write, ‘knowledge does not demand certainty; it demands doubt.’ How did it get to the point where a smart young man like Dominic can believe in a binary, red pill-blue pill world of epistemics, in which there are only two hermetically distinct streams of knowledge to choose from, his preferred ‘truth’ and the other, ‘mainstream’, ‘official’ version, which all those who reject his truth believe without question? Where they can warn of the dangers of confirmation bias even as they practise it? These are questions that the community of conspiracy theorists can’t answer by themselves.”

A couple of conspiracies to keep stewing on though, as we are wont to do. While we were gone, a US government-commissioned report settled on the most probably cause of the mysterious Havana Syndrome not being crickets, as Ed Yong was so certain, but “directed, pulsed radiofrequency energy”. That’s the proper spy stuff. Of course, the 1776 Report was also commissioned by that same US government, so who can say for sure.

And how about that Gatwick drone? What ever happened with that one? ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Can’t solve that one? Let’s raise the stakes. How about the Dyatlov Pass?

“AI art is just a fad”

— Holly Herndon (@hollyherndon) January 5, 2021

Me pic.twitter.com/2wcZKbUsfb

For some reason, the article we’re choosing to link to from MIT Tech Review’s Food issue—packed as it is with excellent pieces about genetic modification, food insecurity, cell-cultured breast milk substitutes, and robot farmers—is this short history of fad kitchen gadgets. Truth told, we want a longer version of same that focusses on all the ones that fell by the wayside. But it’s nice to just think about dumb kitchen tools. Perhaps in the end, all we really strive for is finding new and better ways to make our jerky.

We were as sad as anybody when California Sunday ceased publishing last year. Good, then, to see somebody–Robert Baird at the CJR—finally attempt to explore in depth what Laurene Powell Jobs and her Emerson Collective are actually playing at with all the hundreds of millions they’re pouring into media. There are few answers in this piece, but it’s good to have the right questions asked at this length.

Every time I lose a follower I am proud to have defeated them with my content

— martiñ urbano (@MartinUrbano) December 8, 2020

For just the sheer sensory pleasure of the experience, we’ve probably not reread any article in the past year quite so many times as Patrick Lockwood on Vladimir Nabokov in the LRB. She writes perfectly the joy of a particular kind of vulnerable reading—that full-body, all-senses experience of giving oneself over to time with another mind you know you’ll never truly comprehend, but will never tire of spending time being bewildered by. We can’t pick a particular passage to excerpt, so instead, here’s her Covid-delirium-induced Nabokov bingo card.

We’ll take bottom left on a t-shirt, please.

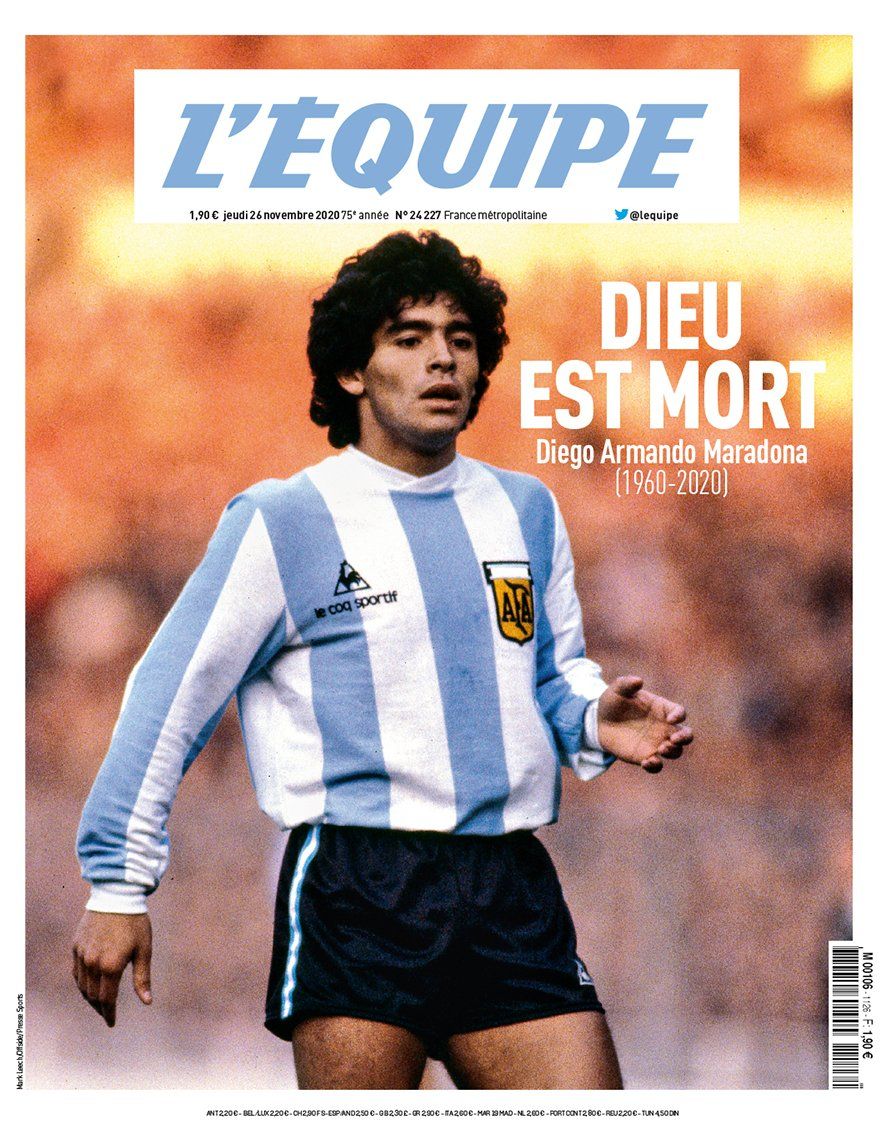

When you don’t send one of these for more than a quarter of a year like this one, you lose far too many greats. David Graeber, Ann Reinking, Charley Pride, Cicely Tyson, Alex Trebek, John le Carré, Michael Apted, Mf doom. So many obits to write, so little time. The audiobook of Graeber’s Bullshit Jobs, for one, has been an important friend through many frustrating work situations in recent times, and a reminder of a few better possible paths forward. But for our favourite quote from any of their obituaries, we hand it over to God himself, the great Diego Maradona.

“I was in the Vatican and I saw all these golden ceilings and afterwards I heard the Pope say the Church was worried about the welfare of poor kids. Sell your ceiling then, amigo, do something!”

The funniest part of modern life is having to be constantly alerted to news of Zack Snyder's Batman movies. Similar feeling to a parent calling to say someone you've never heard of is getting married pic.twitter.com/xdpE18Cm2d

— Jack Vening (@jack_vening) December 15, 2020

Ever since John somehow unearthed this wild Maersk promo video somewhere deep down a YouTube rabbithole, it has not left our thoughts for very long. “We made economies grow, supply chains flow.”

Five verses to that particular song:

- In Lebanon, post-explosion: “New economic pressures are forcing Lebanon’s cartels to do anything to survive—except change their spots. The Lebanese public and the government are increasingly broke, leaving corrupt elites with fewer pockets to pillage. Business cartels are accepting short-term concessions to avoid lasting reform, in the hopes of reactivating stagnant patronage networks in the future.”

- In San Diego, intra-pandemic: “Daniel, the former jet engine mechanic who took on $40,000 worth of scooter debt, says that his scooters have been generating thousands of dollars in revenue each week. Bird demands that he keep 95% of his scooters on the street and keeps the pressure on him even when his scooters are in the repair shop, he says. If he can’t keep up with Bird’s ‘performance metrics,’ Bird threatens to take away some of his scooters, which he fears would lower his daily earnings.”

- In South Carolina, at a particularly bland prison dinner time: “It started when FlavorPros owner Charlene Brach secured contracts for BOP facilities in South Carolina and elsewhere with the promise of very cheap garlic powder, oregano, cinnamon, and other spices. The contracts stipulated that the spices be ‘pure', a requirement Brach apparently ignored, proceeding to deliver products that were, on average, less than half real spice.“

- In Amsterdam, inside the economic doughnut: “In his 2018 review of [Kate] Raworth’s book, Branko Milanovic, a scholar at CUNY’s Stone Center on Socio-Economic Inequality, says for the doughnut to take off, humans would need to ‘magically’ become ‘indifferent to how well we do compared to others, and not really care about wealth and income.’… Raworth cites Milton Friedman—the diehard free-market 20th century economist—who famously said that ‘when [a] crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around.’ In July, Raworth’s DEAL group published the methodology it used to produce the ‘city portrait’ that is guiding Amsterdam’s embrace of the doughnut, making it available for any local government to use. ‘This is the crisis,’ she says. ‘We’ve made sure our ideas are lying around.’” (For more on Kate Raworth’s increasingly noticed doughnut, you could start with what she presented to the Biden transition team.)

- In the Niger Delta, 15 years of fighting later. “A Dutch court ruled on Friday that a subsidiary of the British-Dutch multinational Royal Dutch Shell was liable for oil spills in the Niger Delta in Nigeria in 2006 and 2007, ordering the company to compensate a small group of residents in the region and to start purifying contaminated waters within weeks. The decision was the latest development in a yearslong judicial saga that pitted four Nigerian farmers against the company, and it could pave the way for more cases against the oil company in the region."

Brush The Ethereal Mane Of This Wise, Majestic Horse In The Correct Pattern To Access Your Banking Software. You Have One (1) Attempt Before Account Deletion. pic.twitter.com/g2aQ6kZzmj

— regular gem (@Choplogik) January 27, 2021

A fascinating, majestically, infuriatingly niche paper in Triple Canopy from Jonathan Sterne and Mara Mills on the history of time stretching audio, from Douglas Fairbanks to “Justin Bieber 800% Slower”.

And finally, in this year of missing things, a shout out to friend-of-Buckslip Mike Takasaki and his wonderful, recently launched newsletter “The Plate Cleaner”. It’s mostly about food and cooking but a bunch of other stuff manages to find its way in, too. One of our annual holiday highlights is groggily assembling at Mike and his wife Beth’s place on New Year’s Day, and partaking of the magnificent spread they put out for the occasion. It’s Mike’s way of continuing a tradition begun by his Japanese-Canadian grandparents, though sadly, of course, not this year. In our favourite post so far he writes about the history and making-of Japanese-Canadian chow mein, one of the staples of his annual new year’s spread. Yes, it is its own thing, separate from the familiar Japanese noodle dishes, “derived from Chinese chow mein, taught to the wives of Japanese coal miners in Cumberland, BC by a Chinese man in town in the early 20th century.” Though it’s fair to say that today, no two families make it exactly the same.