1. Things I would have said

I’d meant to write to you the week that the magnolias were opening. I had an essay to share from Ben Dark — in House & Garden, of all places — about how a magnolia’s bloom seduces a beetle into lingering for long enough to pollenate. And about how, after a symbiotic co-evolution with the beetles that started some 30 million years before bees, the only thing that can produce a magnolia is patience. “They are bought in instalments, summer by summer, bud-break to leaf-drop, paid for in time itself.”

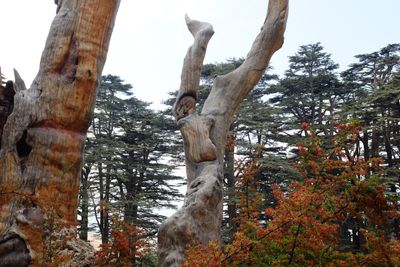

But of course we didn’t buy the best trees in England. There was no way we could. The best trees in England are not for sale. They are wedded to the place they have grown. Within a half mile of that North London mansion there were a thousand trees better than all the stock advertised in the nurseries of Kent, Italy and Holland. Those fragile, aged things had crowns wider than the slow lane of the M20 from Dover. They wouldn’t tessellate, sardine-like, on the back of an articulated lorry, as trussed up Liquidambar styraciflua ‘Slender Silhouette’ would. The hundreds of thousands of pounds spent on plants for the oligarch’s garden got him nothing approaching the quality of the trees at No.4. If you want something as magnificent as the Grove Park magnolias you do what the rest of us do, you plant it and bloody well wait.

But I got distracted. There was a war on. What are you supposed to write about? The trees are still growing. I’m still dusting this year’s pine pollen off of all of my clothes a couple of weeks after it fell. About a year or so ago, just after we last wrote, the Ever Given got stuck in the Suez Canal. There were things I probably wanted to say about supply chains and shipping and how the vast interconnectedness of all things has so many obvious points of failure we’re not prepared for, but it all sort of stayed stuck. They moved the boat, but if you remember, moving the boat did not magically fix anything. Boats get stuck all the time.

Just before the magnolias, I had wanted to send you this footage of Prince as an 11 year old schoolboy in Minneapolis. I didn’t have anything to say about that, I just thought it was cool. And easier to talk about than the IPCC’s "Atlas of Human Suffering” that had been lingering in all the accessible bits of my brain, undeniable and unfathomable.

In the early days of the war, I’d wanted to share with you Yegvenia Belorusets’s Kyiv diaries, as she tried to make sense of the shifting configurations of hope, fear, defiance, and murder in the streets around her. The question she was asking, the question impossible to answer — “What happened to us all that this became possible?”. If we’d sent this to you in the earliest days of the war, I might have included an extract like this:

The city is sinking into spring fog, but it is still cold. Since yesterday, here, in the center of Kyiv, you can tell a story about the war on every street corner. Almost every intersection is guarded day and night by armed members of the Territorial Defense. There are more groups of saboteurs in the city, more violence. I look with relief into the eyes of the men and women of the defense. In one of the faces yesterday I recognized with amazement a barista who was popular in our neighborhood because he painted particularly beautiful swans on the milk foam of the coffees.

Outside, I hear another explosion. At such times, fear overtakes me, and I think about how to save myself and the people I love from this situation. It is always a chain of relationships that I think about, it is not only my father and mother, but also my aunt who is lying at home sick and weak. And not only my aunt, but also her whole family, and then I see other connections that are hard to break.

The answer is to keep everyone safe, not just individuals. Now is the time to act bravely and find strong, effective means against the aggressor. In my imagination, a hundred variants are already playing for how all this can stop, how the war will end, at this specific moment. Then I imagine us dancing in the streets.

I might have accompanied it with a picture of the label of the Georgian wine I was enjoying at the time, “20% of Georgia is occupied by Russia”, it says, with Georgia in the shape of grapes with the appropriate chunks picked off. It’s a good wine. Smokey.

Yevgenia’s left since then. Those diaries are now out in print and were presented at the Venice Biennale. For what that’s worth.

I wanted to write about my conflicted thoughts on the closure of the GarfieldEats restaurants. And about how prolonged grief was added to the DSM, an addition which makes far too much sense to me and my own pathologies, even as I read all the expected reactionary pushback that always accompanies any attempt at deepening our understanding of mental illness.

I wanted to find things to say to you when truckers, or people playing them on the internet, took over our capital and the feds invoked a state of emergency that is still being argued about today. But I had little other than frustration to offer there.

And then, at about the time the asperitas clouds were settling over Lake Ontario, there was this big sprawling piece about how particle physics can no longer figure out its fundamentals, now that they can no longer be sure that big things are made of small things, and that the biggest thing the colliders have taught us might be that we have no idea what’s natural at all. That’s exactly the sort of thing I would have written to you about!

“Some people call it a crisis. That has a pessimistic vibe associated to it and I don’t feel that way about it,” said Garcia Garcia. “It’s a time where I feel like we are on to something profound.”

But look, I didn’t write to you about any of these things. In the underground malls that snake beneath downtown Toronto, life is returning, but not as it was. The war is still on and as I write, sitting on the edge of an island a few hours north of Toronto, the water lapping at the shore, listening to a brown thrasher in a tree on the other shore singing the song of every bird it’s ever met, Roe v. Wade has been overturned and I’m trying not to lose myself in the dissent, a heartbreaking document which imagines, yes, like the story we all know, of the ultimate need for flight to Toronto.

So let’s just figure what to keep talking about together, yeah? Thanks to everyone that wrote in response to our little “we’re coming back” email. It was so very lovely to hear from all of you with such warming (and surprising!) thoughts about what this email means to you.

We’re glad to be back. You mean just as much to us.

Onwards!

Patrick

ps. Unsubscribe link is down bottom, or you can manage your account here!

2. Things you could listen to while you read this

Here’s another one of these mixes Patrick made, a few months back now, but it has some good hurricane sounds, even if it’s maybe a bit wintery for post-solstice.

And here’s an excellent playlist from Syrian American ethnomusicologist Dunya Habash in The New Humanitarian, gathering together the music of exiled Syrian musicians she loves.

As an aside, being caught in the steely grip of relentless surveillance capitalism is more fun if you ditch the notion of the algorithm and instead posit we each have a personal Advertising Goblin, a harried, overworked little critter who's really trying his best.

— Travis Johnson (@CelluloidWhisky) February 15, 2022

3. What’s the harm in taking that one, too?

“If a person should want to commune with infinity once more, then it’s enough to go online. Here, the overwhelming feeling that there is too much of the world teaches a certain cautious resignation—I’ll just go on my way, learning to ignore the curiosities that beckon on the side of the road, like Lot fleeing a burning Sodom with enough willpower not to turn around and look back, unlike his overly curious wife.

Let’s call it Lot’s Wife’s Syndrome now whenever we get stuck in front of our screen—a kind of contemporary catatonia. This syndrome affects millions of teenagers and incels who, particularly during the pandemic, despite warnings, have looked at the burning cities and been unable to tear their eyes away again.”

At Words Without Borders, the great Olga Tokarczuk seeks a new terminology for us to make sense of our “new experience of the smallness of the world” and its overwhelming finitude. It’s an empathetic and constructive essay, befitting Tokarczuk’s lately epic tendencies that starts in despair, but finds its way to some sort of toolkit for looking forwards, a lexicon of ideas for understanding this mess around us as a complex, and navigable, system of interlinked stories.

Our generation and previous generations were trained to tell the world: YES, YES, YES. We kept repeating: I’ll try this and also this, I’ll go there and then there, I’ll experience this as well as that. I’ll take this, and what’s the harm in taking that one, too?

Now alongside us there is a generation that understands that the most humane and ethical choice in this new situation is learning to say: NO, NO, NO. I will give up this and that. I will limit that and that. I don’t need that. I don’t want this. I will let this go.

We liked this alongside Hari Kunzru’s Harper’s essay Broken Links, a sort-of memoir of the increasing grip of being extremely online, which is admittedly a tad nostalgic in a “we used to have to look things up in the phonebook” sort of way, but also captures a moment of what, at the time, felt like utopian possibility, but showed us the way to right where we are.

Looking through my box of club flyers and reading yellowing printouts of emails from Croatia, I realize that the dominant feeling at that moment, when the transition was happening but had not yet become general, was of something enormous coming over the horizon, something transformative and possibly terrifying, but about which we could say almost nothing.

There was a phase when friends would ask me to show them the internet. I would tell them that it was a network of computers connected to telephone lines. As my superfast 14.4-Kbps modem began its wheezing handshake, I noticed one friend clutching the side of his chair, as if bracing for impact. As the little white telnet window opened up and a block of text welcomed us to LambdaMOO, an early online community, I could feel his disappointment. Where was the ecstatic cyberpunk rush? Where was the surfing? I had to explain that it wasn’t there yet, not quite. Soon, I said. Soon everything would change.

Pair with Katie Mackinnon’s study of the eulogies left behind by site owners in some of the more blinged out corners of Geocities. As they recognized its decline they decided to move on, sometimes “having either grown up or grown tired”, but often enough in anger at changing conditions of the relationship with the platform itself.

The platform eulogy in Sunshiney’s Cyberpet Adoptions page in November of 2002 echoes what other GeoCities members describe, which is the inability – for various reasons – to continue maintaining pages at the level they were before. Others write that they received too many mean emails (cottage/2890), do not have enough time(cottage/4225), are a grandmother and can no longer keep up (glade/7438), think their homepage got too big(meadow/1024) or simply grew up (meadow/1479). Sunshiney’s homepage, prior to removal, engaged deeply in the politics of creative content fair use, whereas other homepages with her level of popularity might not have been as inclined.

And not looking backwards but looking from deep inside the dark pockets of now, Joshua Citarella explains in tactical detail how he deliberately infiltrated some of Gen Z’s radical online political shitposting communities on Discord and elsewhere, to quietly nudge them, by way of meme, away from Ted Kazcynski and towards Mark Fisher, and perhaps ultimately to engage in political organization and electoral politics (“Perhaps that last part was a bit too ambitious lol”). If you’ve ever seen a Capitalist Realism meme on your instagram feed, this is how they got there.

The strategy was to plant a series of connected references that nudge and guide their interests over time. You are entering through the bottom of the funnel to build a pipeline out. This process will require new links, nodes and stepping stones that join to form a reference chain. It may take two weeks to familiarize the community with one reference, the next might take days, while others could take months. Each successive link should build on the ideas of the last. Each link must feel causal and intuitive. Adjacent ideas should interact and reinforce one another, but when taken as a whole, the starting and end points may be radically different.

I'm worried the 10 great warriors I summoned from different periods of history to fight in a tournament have started a second group chat I'm not in

— Jack Vening (@jack_vening) May 5, 2022

4. Things we made that we could’ve told you about

Here’s Eli’s very important reporting in The New Yorker over the time we’ve been gone: I am a Man, and I Run Hot. I Have Been Watching This Man’s Laptop for Thirty Years. I Cannot Being to Tell You How Proficient I am in Microsoft Word. And more!

Chris F and Patrick made a series of observational videos for Live Magazine as part of the Bentway Street Summit here in Toronto. Which merely entailed visiting a handful of street intersections around the city, setting up our camera and sound gear, then letting things roll. You might call them exercises in what Georges Perec called the “infra-ordinary”. It was fun! And maybe a concept we’ll do more with in the coming months. (Perhaps as our answer to this classic of insomniac, late-night Toronto TV from the ‘80s.)

Here’s a review Patrick wrote for The Georgia Review on Maria Stepanova’s extraordinary In Memory of Memory — a masterful book about trauma, and how memory rewilds it. And here’s Stepanova back in March, in the FT, on the war of Putin’s imagination.

Survivors, all of us included, Stepanova thinks, tend toward a habit to define our present by the traumas of the story that’s arrived with us, passed down and obscured through retelling and haphazardly preserved documentary evidence. These survivors, she writes, are bound to a lifelong quest for “something to remember and to call back to life at the expense of their own today.”

5. The is-ness of what is

Alex Molotkow’s Crush Material Substack is a sporadic but occasional joy. Here she is on Arthur Russell, by way of Renoir and Iris Murdoch.

“Russell’s art accepts the mutual struggle; it’s at peace with the unholdability of longed-for things and the is-ness of what is. It elevates me, lifts me out of bad habits of mind, and helps me to meet the world on its own terms, if only for a bit. That makes it virtuous, and I think virtue in art is a characteristic, perhaps, like color palate or key signature — a quality, not a judgment of value.”

We’re suckers for these New York Times zoom-about-the-page art history things. A Messy Table, a Map of the World is sort of about the history of Dutch still life, but as it unfurls, it begins to ask much more interesting questions about what we’re looking at — “how did all that stuff end up on the table anyway? And why this stuff?”

Sick of people calling everything in crypto a Ponzi scheme. Some crypto projects are pump and dump schemes, while others are pyramid schemes. Others are just standard issue fraud. Others are just middlemen skimming of the top. Stop glossing over the diversity in the industry.

— Pat Dennis (@patdennis) April 25, 2022

6. From now on we all walk through walls

This space that you look at, this room that you look at, is nothing but your interpretation. Now, you can stretch the boundaries of your interpretation, but not in an unlimited fashion – after all, it must be bound by physics, as it contains buildings and alleys. The question is, how do you interpret the alley? Do you interpret it as a place, like every architect and every town planner does, to walk through, or do you interpret it as a place forbidden to walk through? This depends only on interpretation. We interpreted the alley as a place forbidden to walk through, and the door as a place forbidden to pass through, and the window as a place forbidden to look through, because a weapon awaits us in the alley, and a booby trap awaits us behind the doors. This is because the enemy interprets space in a traditional, classical manner, and I do not want to obey this interpretation and fall into his traps. Not only do I not want to fall into his traps, I want to surprise him.

This is the essence of war. I need to win. I need to emerge from an unexpected place. And this is what we tried to do. This is why we opted for the method of walking through walls ... Like a worm that eats its way forward, emerging at points and then disappearing. We were thus moving from the interior of [Palestinian] homes to their exterior in unexpected ways and in places we were not anticipated, arriving from behind and hitting the enemy that awaited us behind a corner ... Because it was the first time that this method was tested [on such a scale], during the operation itself we were learning how to adjust ourselves to the relevant urban space, and similarly how to adjust the relevant urban space to our needs ... We took this micro-tactical practice and turned it into a method, and thanks to this method, we were able to interpret the whole space differently ... I said to my troops: ‘Comrades! This is not a matter of your choice! There is no other way of moving! If until now you were used to moving along roads and sidewalks, forget it! From now on we all walk through walls!

(Aviv Kochavi, Chief of General Staff of the Israeli Defence forces, quoted by Forensic Architecture’s Eyal Weizman in this LRB article on, amongst other things, the use of Deleuzian critical theory by the IDF.)

“Biologically, the saguaro can’t claim any particular superlative: this is not the world’s tallest cactus, nor the largest, nor the longest lived. It’s simply beloved. “ A nuanced, far-from-simple exploration of that beloved, most-postcard iconic of cacti, from Boyce Upholt in Emergence. which unfurls the story of the rights of nature by way of the most postcard-iconic of cacti – considered a legal person by the Tohono O’odham Nation – a person suffering through climate change, construction, brutal border politics, and the odd deranged shooting.

The idea of writing a cactus’s rights into law may seem odd within the context of our particularly American concept of freedom. The US legal system has been built mostly to protect what philosophers call “negative” freedom. It focuses on removing constraints on our human freedoms, on ensuring that no one can tell us what to do. David Grundman, the Phoenix man who was crushed to death by a falling saguaro, offers a perfect emblem: a man in a desert, shotgun blazing. This is a what’s-mine-is-mine freedom, an ability to lay claim and lay waste, to clear-cut the vegetation, to pump the water, to strip-mine the copper, without a care for what happens on the other side of your property line—a freedom ironically dependent on the construction of fences and walls.

The Indigenous concept of community, meanwhile—of reciprocal relationships between its members, whether human or nonhuman—suggests a “positive” conception of liberty: freedom as the capability to flourish, as the power to become whatever you’re meant to be. But this can be accomplished only if we all work together—if every member of the community receives support and respect and aid.

One of the most extraordinary books we’ve read this year is the collected writings of imprisoned Egyptian activist Alaa Abd el-Fattah in the time since Tahrir Square, You Have Not Yet Been Defeated. The collection, brought together by a collective of friends and comrades, traces a decade of rising waves of hope and grief, defiance and defeat through contemporaneous dispatches, sometimes on Twitter, sometimes smuggled out of a cell. It’s ultimately, in the end, a manifesto for the right and responsibility to fight for living beautifully. The biggest question we were left with at the end of it was about the heartbreaking ambiguity of the title, and how it changes when you give the emphasis to “You” or“Yet”. Here’s Naomi Klein’s intro, anyway. As she puts it: “Most of all, it must be read for what Alaa has to tell us about revolutions—why most fail, what it feels like when they do, and, perhaps, how they might still succeed. It is an analysis rooted as much in a keen understanding of popular culture, digital technology, and collective emotion as it is in experiences confronting tanks and consoling the families of martyrs.”

Sometimes the archives of fights for living beautifully, and freedom as the capability to flourish, show up in the places you don’t expect, like — in this beautiful piece by TM Brown — in a box of old cassette tapes left behind in a house on Fire Island, telling the stories of mutual care, and defiance, and partying, that defined that place at the height of the AIDS epidemic.

7. The bit where we asked Eli to pick a video from whichever strange corner of YouTube he’d been lost in

Warning, Phish fans ahead.