1. Maybe I am like Tchaikovsky

Emahoy told me she never wished to be famous, that she wanted her name to be written in heaven, not on earth. She admitted that the connection people feel to her music does mean a great deal to her. ‘Maybe I am like Tchaikovsky,’ she said with a sad smile. ’He didn't believe in his music either. But people like it.’ Before I left her bedside for the last time, she reached out for my hand. She didn't have a lot of strength but something about that grip was unconquerable. Go through life being strong, she ordered me. Don't be told no. Fight for equality. Those were her parting words.

— Kate Molleson, Sound Within Sound

There are certain musicians who, when you hear them for the first time, something fundamental clicks into place. A music so perfectly unfamiliar, and yet so perfectly right, that it not only makes new kinds of sense but it feels like it fills in a space previously missing in your understanding of the world and how to move through it. I’m thinking here about, say, Arthur Russell, or Julius Eastman, or Townes van Zandt, or Pauline Oliveros. Those are my examples. Yours are probably different. But you know what I mean — the ones that reshape the boundaries of what you thought music to be.

There are so many words people default to when they first hear the music of Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou, the Ethiopian nun who lived out her days in Jerusalem — as with the headline of this recent New Yorker appreciation, a popular one is “otherworldly”. Whatever’s going on with that piano, it’s hard to place. There are modes of playing that cross cultures and histories, but come from somewhere entirely their own, impossible to notate in any form we have. There’s elements of the Ethio-jazz around her, sure. And elements more classical. But there’s something entirely other, too. When I first heard Kate Molleson (whose book I link to above is really great and you should read it) engage with Emahoy in this BBC Radio 4 documentary, I was a little confused by its title — ”The Honky Tonk Nun”. What would it mean for this reverent, calming drift — something to do with a piano that didn’t quite sound like anything else that had been done with one — to emerge from the back of a sticky old bar, somewhere next to the pool table, small beams of light shining in from holes in the wall?

Emahoy lived a big life. A grand one. Unusually so for a nun. It was bound closely with Ethiopia’s 20th century, from growing up in the privileges of Haile Selassie’s inner circles, to boarding school life in Switzerland, where she first learned to play. Then, back in Addis Ababa, the fascists came, captured her sister, and murdered her brother. In exile in Naples, she found an abandoned organ in a monastery, and she figured out how to play it. She died last month, and that music’s been rolling around my head and ears ever since. Not just the few scraps of recordings that already existed, the stuff that most people had found their way too, but this well-timed (surely not coincidental) new release of so much more material from those archives, Jerusalem.

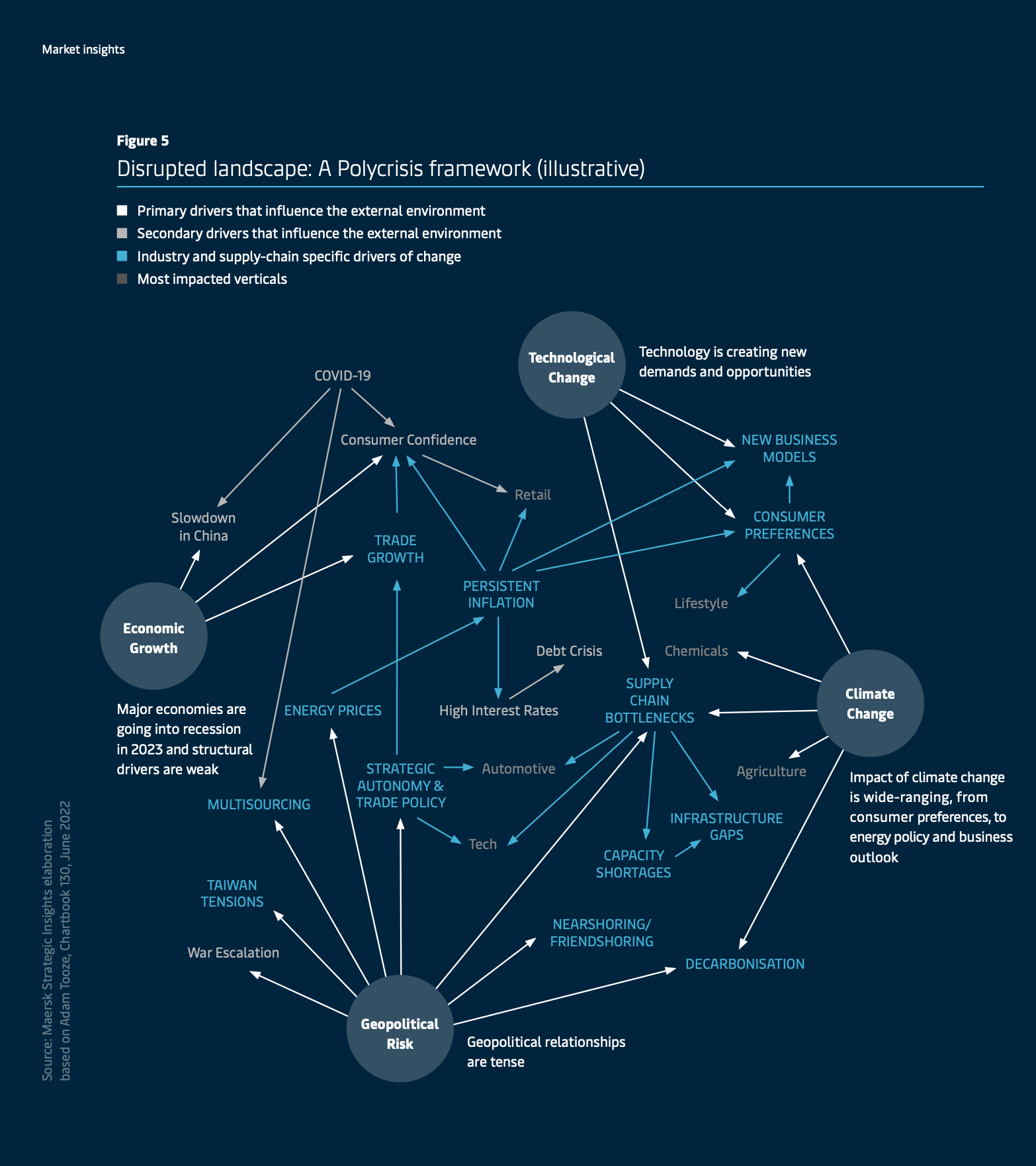

While I was listening to Emahoy, I was doing some research work looking at ways the languages and anxieties of contemporary crisis are seeping into the mundane everyday deck-speak of business. In the annual report of Maersk, a company deeply tethered to and sensitive to the interconnected fragilities around us (even when they’re rolling out banger corporate videos celebrating their role in all this), you can now find diagrams like this one:

Talking to friends about a downturn, noting and sharing with others how the struggles felt realer and more immanent than they had even a year ago — and also noting how small those struggles felt when placed against larger lives and broader narratives, I got to wondering, where do I sit on this map? How is it buffeting me? Thinking about WhatsApping with an old friend in Khartoum back during lockdown, the photos she sent me she'd taken of refugees from Ethiopia struggling over the river border into Sudan, fleeing horror. On the Sudanese side, there was a coup, and the horror came back, and now there's civil war again, though as Nesrine Malik writes, it's a mistake to think of these things so linearly. Sudan's tragedy, she writes, "is that of a country that dared to ask for more and is now being punished for it." And the joining threads of that polycrisis keep snapping back into place, exiling those at its edges.

I don't know a single Sudani who doesn't love Sudan to a fault.

— Yousra Elbagir (@YousraElbagir) April 29, 2023

An entire generation was forced into exile during the Nimery & Al-Bashir era. In the early 2000s, many of them returned to rebuild.

Now, another era of displacement that some are rejecting.

On the speakers, Emahoy’s “Quand La Mer Furieuse”, her recollection of the rolling waves on which she floated as a child from Africa to Europe, on the first steps of a journey defined by a creed.

Go through life being strong. Don’t be told no.

– P

ps. Whatever’s going on with Twitter – not a hell topic we felt like spending much time on this issue, tho RIP to the one blue check we held between us all, but we’re still embedding Tweets because we haven’t figured out a better way to throw stupid gags into the mix. Any suggestions?

2. The body is a vessel for an infinite substitution

“Maybe this May will be the last of the bad months, before things start to get better…”

A couple of years ago, back when we were emailing you a little more regularly, Chris F and Patrick set out to make a documentary about that moment we were all living through. We weren’t sure why, but we thought there was something that should be captured that might come in handy later on. Loosely inspired by Chris Marker’s Le joli mai, we traveled within the limits we were allowed at the time — that being Toronto’s city limits — and from a distance of six feet, we asked others about what they were living through.

The end result is May Flowers, our first feature-length documentary. We’re still making plans for finding it a home in theatres and the like, but while we do, we’re pretty excited to share the trailer with you. It’s a strange feeling, journeying back to that time, and thinking about what we choose to hold on to, and didn’t. Let us know what you think?

3. Did we learn anything?

We are urban African American Futurists who pioneered yet another sonic gift to the world. We are taking the sound into the future. The question becomes: will a history of greed and ignorance repeat itself and unknowingly make us irrelevant? Did we learn anything?

- So reads the mission statement of Underground Resistance, the Detroit music label at the heart of this New Yorker story by good friend of BS T.M. Brown, about two very different techno museums, the disparity of how Europeans fund and preserve cultural memory vs. North America, and who gets excluded when cultural history gets institutionalized, or neglected.

What happened? Gopniks saw some anime kids wearing weird clothes in a mall, ask them what’s up with their outfit and beat their faces in. The anime kids got stronger and beat up the gopniks. This became so funny that the internet started calling the anime kids ‘PMC Ryodan’… Other Gopniks weren’t happy with this, went off to find this ‘PMC’ and started beating up random anime kids who fought back. The police turned up to stop the fights and made arrests, then the media started to write that ‘leaders of the aggressive group PMC Ryodan were detained’.

- On the flipside of the role of Discord in US intelligence leaks, here’s an angle on its role on the Russian side of this mess. This Bellingcat investigation of “PMC Ryodan” is a weird ride — in which Discord kids shitposting and bonding over anime allegiances become bound up in a Satanic Panic-level fear, find themselves face to face with legions of tracksuited enforcers, and still seem to be kind of enjoying it?

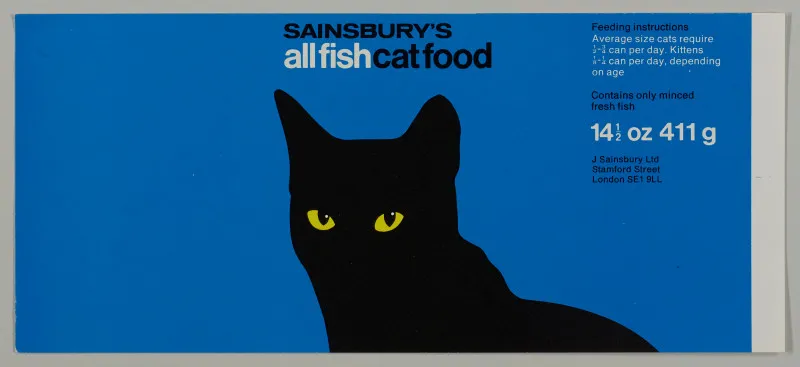

Wandering the aisles of a Sainsbury’s now, you don’t feel like you are navigating the architecture of war or embracing modernity, but languishing in a place outside of time in perfect, frictionless ease. (Ease, it bears saying, is not the same as simplicity.) But maybe this new aesthetic, which is more cluttered and less engaging, designed to promise but never to provoke, is true to the kind of shopping we do today. If we were to revive those designs from the 1960s and 70s, no matter how modern they appear, we would be lying about who we are.

- Thoughtful, stunning eye candy from Ruby Tandoh in Vittles, one of our ever-favourite newsletters, in which she explores the design history of Sainsbury’s supermarket own-brand product packaging. Some gorgeous constructivist influences going on, but this cat food is the best.

“In a way, we’re fighting modernization, because nobody wants to pick up a manual handsaw,” said John Awonohopay, lumber operations manager for Menominee Tribal Enterprises, the company that oversees the forest. “Think of it as a garden. Right now we’ve spent 150 years plucking all the weeds, and have it pristine. But we can’t harvest the pristine fast enough.”

- This issue’s forestry management content comes to you courtesy of the Menominee in Wisconsin. When looked at from a certain angle, and when the work is managed by people who understand their role in the larger story, the sawmill can become not so much a tool of preservation as a tool of collaboration with the trees.

- Ok maybe not entirely no Twitter news. It was pretty good to meet the real Dril, at last, before the lights get turned off. Does the bit still work when we know the ultimate shitposter is just some guy named Paul? (Ok fine, and of course also the Willy Staley piece was good. A Type of Guy who gets Twitter better than most.)

descartes in 1637: pic.twitter.com/KTXLmxCs3O

— zach silberberg (@zachsilberberg) March 1, 2023

4. “Say no to creative rent!”

So bellows our dear Buckslipper Chris Lange proudly, Braveheart style, as he launches the Anti-Subscription Software Catalogue, a careful and lovely database of “non-subscription, free, libre, open-source, and one-time fee software — which can provide relief from monopolized and financialized platforms.”

We slip into the inevitable habits, right? We of course cut the above movie trailer on a bunch of Adobe tools, because we pay the subscriptions by default, so it’s all just there.

That’s partly the reason we’re a bit stubborn with this email these days, about sending it with open source tools, on a platform we own, not so subject to the whims of VC-backed startups who might decide they’d rather they were a social network instead, or whatever. Lange’s work here is a small and good gesture that has us thinking again about how the tools we choose (handsaws, sawmills, audio editing plugins) shape the work we do and the world we want to build.

We all love it when they add a really dumbass movie to the criterion collection…….it’s like when a dog is mayor

— Naomi Skwarna (@awomanskwarned) April 19, 2023

5. The Parallax Test

We started a short experiment of a little Instagram newsreel series — there will be more of these, if that’s a platform you’re still on.

Some kid just showed up at the sandbox with an excavator toy identical to the one my kid lost yesterday — but it isn’t my key suspect. Could be a coincidence, could be that I have this thing all wrong…could be a lot of things. But I wasn’t prepared for this.

— willy 🌜💧 (@willystaley) April 16, 2023

6. Offshore Wind Turbines Offer an Alluring Tone

I feel at times akin to how a wild animal might feel peering out from a deep forest at a blinking neon sign on the edge of a road, advertising some mysterious product.

In part, this is because of the strangeness of how the term “climate fiction” has spread, and the way the term has made various writers and factions claim territory, even as marketing has commodified it. It all makes the baby raccoon in me want to retreat further into the woods, because even the apparatus of the terminology has become mired in all-too-human foibles and irrationalities.

Jeff Vandermeer goes big on the history, purpose, and pitfalls of the “cli-fi” genre, and what the heck it means to offer hope, or not, in the end. There’s a life’s worth of reading suggested by his references here, and we’re excited to dig into them. For starters, Ling-Li Tseng’s Disaster as Opportunity is offering to us what Vandermeer suggested it did for him.

Meanwhile, it seems baby cod are really into the sound of offshore wind farms. In Noema, an appreciation of hydrophones, and devices to help whales sing boats out of their path. And as Patrick begins to ponder hitting the road back to Newfoundland once more from Toronto, he’s hoping this handy guide for how lichen presence can indicate vulnerability to sea-level rise will prove useful. At least until the Sargassum Belt arrives and makes things a whole lot messier. Go for the “sargassum anxiety”, stay for the renderings of sargassum-fighting robots.

And all of that out there — the vibing cod, the singing whales, the sargasso sea — doesn’t really belong to anybody. It should transcend our squabbles, argues the new “biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction” treaty, roiling its way towards ratification for 15 years now, now fully agreed, closer than ever, but not quite close enough. (UN treaties being famously problem free and rapid in their global uptake.) If done right, some argue it might offer “a [blue] economy that centers justice and environmental security and actively manages for marine protection and avoidance of environmental impacts”.

German and English texts commonly describe a witch or wizard keeping a toad familiar, a relationship built upon a parasitic practice of bloodletting in exchange for the familiar’s obedience. While traditionally it was the witch who gave suck to the familiar, we read in some confessions that the toad would be fed and then “milked” for a substance that could then be used in ointments and other malefic practices.

Nothing more to say about “Toad Lore: The Natterjack at the Edges of Occult History”. Just enjoy it. Perhaps while you wait for your pre-order of the Mycology board game, created by an actual fungi professor?

The problem with cultural dissent in America isn’t that it’s been co-opted, absorbed, or ripped-off,” cultural historian Thomas Frank wrote in The Baffler in 1994. The countercultural idea, having offered itself to business interests, was “no longer any different from the official culture it’s supposed to be subverting.” This seems truer today than when it was written. The internet age, despite its promise of endless connective potential for the most outlandish human activity, has mainly led to cultural productions that are ready-made for the hosting, use, and profit of global companies—it often seems there’s little alternative. How would a mass countercultural movement even form today?

For The New Republic, Michael Friedrich considers a history of SST Records that serves partly as nostalgia, partly as a warning, partly as a reminder that once upon a time, another world seemed possible.

And speaking one last time of musicians who’ve changed our perceptions of what music even might be, we appreciated this Guardian profile of the “grief, hallucinations and exhumed violins” of Richard Skelton. (And as a chaser, here’s an interview Patrick did with Richard a lifetime ago, in a magazine he used to edit that sadly announced this last month that it’s closing up shop. Salutes and thank yous to Dumbo Feather! You had a good run! You opened up worlds for us!)

I do not give a flying FUCK about Fonts... Weirdo shit. https://t.co/bScWTlSi8R

— ICE T (@FINALLEVEL) March 28, 2023