Verbatim

In a scene-setter for her new book Democracy May Not Exist, But We’ll Miss It When It’s Gone in The Nation, Astra Taylor surveys a couple of centuries of thinking about democracy, and how those foundational best-laid-plans can hold up when punched in the face by populist regressivism and the existential threat of climate change. What’s always set Taylor apart (and what draws us back to her repeatedly) is her ability to find tangible hope, earned optimism, and constructive paths forward, even in the most fraught of scenarios.

Against this knee-jerk apocalypticism, this loss of faith in liberalism’s prospects, this toxic longing for a whitewashed past and an oligarchical future, belief in democracy as a viable project of collective self-rule is, in itself, a radical act. […]

I came of age in the nineties and aughts, after experts declared that we were at the end of history. The message, received loud and clear through a kind of cultural osmosis, was that protest was over and the future would simply be more of the same. Though some brave souls tried to buck the trend, conventional channels tended to portray engagement in social justice as risible and démodé. Feminists were mocked for being frumpy artifacts, antiwar protesters ignored as a hippie hangover from the sixties, and union organizers dismissed as specters of a discredited socialist era, destined for the dustbin. I was schooled in a postmodern theory that celebrated apolitical pastiche, was told that Marxism was a defunct “meta-narrative,” and that faith in progress would lead only to tragic ends. Instead of caring about the world and what might happen next, we were encouraged to cultivate an attitude of ironic detachment.

A new cohort of progressive activists has upended these convictions. Citizens young and old have woken up to the realization that social movements, updated and evolved, are a life raft. They understand that social media is no magic bullet and that organizing today requires the same slow and steady work it always has. (Indeed, effective organizing may now involve more work, not less, to combat the negative behaviors that social media affords and incentivizes.)

Things

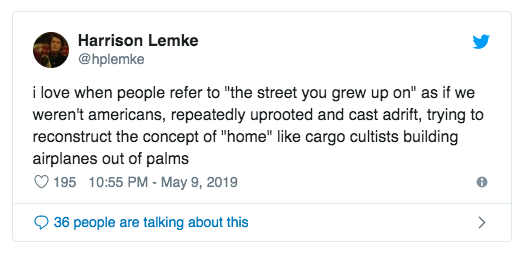

Despite Taylor’s painfully accurate account of growing up on the mainstream left in the nineties, nostalgia continues to offer a hazily different narrative. Off the back of the ongoing decline of the Instagram aesthetic, as the platform (and user desire) shifts heavily towards the ephemeral, Rosie Spinks wonders at Quartz whether we might be seeing the pendulum swing away from perfectly crafted, high-achieving influencer culture and back towards good, old-90s-fashioned slackerdom. We’re not really buying her argument, nor does it feel like what the world needs now is for Z to drop out like X did (unlike the ur-slackers, all evidence to date suggests they absolutely will not), but there are seeds of something shifting on the style pages that, we think, are worth watching as they grow into the pages beyond. It’s just… maybe in the face of what’s in front of us, a pendulum isn’t the inevitable reaction?

Even today’s mainstreaming social media backlash reveals how we continue to cling to the myth of the lone genius/inventor/creator. The NYT provided Zuck’s Harvard roomie a platform from which to issue his unsophisticated analysis and simplistic solution to Facebook’s dominance, as if his proximity to the boy-Zuck gives him some privileged insight and authority (remember back when that same man thought he could save media by pouring money sloppily all over The New Republic until it nearly imploded, leading bystanders to describe him in The Washington Post as “a lame mogul and a metaphorical small person”?). Read Ian Bogost in The Atlantic for both a better sense of the social media soup out of which Zuckerberg emerged, and a more complete picture of his transgressions beyond traditional anti-trust.

Late last year, we linked to some fascinating reporting from inside the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) that suggested a rift growing within the international science community regarding the place for economics in ecology. There was real fear that the results of the IPBES report would be watered down by political considerations and establishment science, and that it would be difficult for nuanced arguments about the importance of biodiversity, and the voices of scientists from smaller countries, to cut through. As you’ve no doubt heard, that report landed this week and it’s a bleak blockbuster, drawing the undeniable outlines of the sixth mass extinction with scientific precision, and (here’s the bit where we hope policymakers might actually be forced to listen even a little bit), the devastating effects of this loss of biodiversity on every single aspect of life on this planet, even for us humans. It’s worth reading the IPBES’s summary document, an unsparing catalogue of our devastation. And as to the internal politics, it’s also worth reading between the lines of the panel’s own internal review of the report, which lauds the science but is politely scathing where it needs to be, arguing that “building the evidence base is necessary but not sufficient” and that the scientists “should not see assessments as end products.” In other words, it’s one thing to articulate just how horrific a situation we’ve created, but unless organizations like this (even if not the scientists themselves) turn their attention equally to actionable policy and solutions, they’ll be ignored until the end of days on the only rotating habitat floating in space that we’ve got.

mixed reviews). Acker is now the subject of a show at London’s ICA, its title — “I, I, I, I, I, I, I, Kathy Acker” — implicitly acknowledging Acker’s influence on the now trendy genre of auto-fiction, especially in its more transgressive or experimental iterations. Over at NYR Daily, Lisa Appignanesi breaks down the show while reassessing Acker’s position in the culture, and how her “transgressiveness and frank avowal of desire was radical at the time, but in ways that don’t necessarily track comfortably with contemporary feminisms.”

The science is finally settled: penis extensions don’t work.

Beyond Meat says it provides not a veggie alternative to meat, but an alternative plant-based meat. After the IPO earlier this month, $BYND is now valued at $4B+, based on the proposition that beef is energy intensive and unsustainable. Like Tesla, Beyond Meat’s big bet relies on massive economic shifts, and it seems to appreciate the cultural dimension of these shifts even better, with the promise to look and cook like real meat. That’s a good start, but can it also signal ambition and status like real beef?

At African Arguments, a series of articles surveying how language — from creole to Kiswahili to Nigerian pidgin — has shaped and created society and identity in culturally contested spaces across Africa. As Nanjalya Nyabola writes in her introductory essay: “There is no grand objective with these essays – really this was a project that we indulged in simply because we could. For African writers and thinkers, that is political enough. Today, to be an African is to have too much of your thinking and theorising forcibly directed towards grand, ill-defined concepts like “development”. Sometimes a meandering walk through a set of ideas that make no meta-claims beyond asserting their existence is political statement enough.“

Vox, Kaitlyn Tiffany tries to figure out just which vegetable the gut doctor has been begging us to throw out for what seems like years, and we’re absolutely here for it. (And it also gives us an excuse to link again to the evergreen Awl (RIP) classic, A Complete Taxonomy of Internet Chum.)

It’s tough times down at the helium mines (mostly, it turns out, because there aren’t actually helium mines), and party balloon companies can’t keep enough stock to satisfy the planet’s desire to have a funny voice for a minute. (There are, of course, abundant other uses for the gas we’d just presumed was abundant, but as we go down the rabbithole on this one, it seems the party companies are the only sources making any squeaky noise, so we’re not sure how much of a real problem this is, but we’re fascinated.)

Medium’s new Human Parts vertical on the political category that is “motherhood”.

The war against ISIS in Syria was in part framed by US and coalition forces as an intervention to protect vulnerable populations from the predations of the terror group. According to a recent study, however, US-led military actions killed far more civilians than previously reported.

Khachapuri wars: can everyone stop calling Georgia’s national dish ‘Armenian pizza’

Netflix and Amazon Prime Video can be great places to launch the films and careers of independent filmmakers. The streaming platforms need not worry about limited shelf space or cinema screens, so they have focused on building the biggest libraries with something for everyone. But Amazon has never even pretended at the sort of creative community that Google has relied upon for YouTube, or Apple with the App Store. And now Amazon is disappearing some independent films from Prime Video, bringing the same tight control to the platform as they have always exerted over their shopping marketplace, where third-party retailers live in constant fear of being buried in biased search results or replaced with Amazon Basic alternatives.

Quite a few of you wrote last week to take us up on our offer of PDFs of an old Alpine Review article that we really should have put online back in the day. We don’t have anything similar this week (though that offer still stands), but damn we love hearing from you.

If you’ve got anything going on in your world that you want buckslip dot email readers to know about, just shout, eh?