Things

At Longreads, Eva Holland writes on the fight over the future of the caribou herds in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. As Holland acknowledges, this isn’t a new story, and for the people of the Gwich’in nation whose way of life is intimately tied to these calving grounds, she’s merely the latest of a relentless parade of well-meaning writers who’ve come to throw their recorders on the table. Does it help to keep telling it? Well, what else are you going to do? “For these people, I was both an imposition and a necessity. They would answer my questions about why the caribou matter, they would suffer my intrusions into their living rooms, my gazing at their family portraits, my minutely detailed notes about how they dressed, what they ate, where they lived – they would do it all, over and over again, in the name of their own survival.”

We throw the word “Anthropocene” around a lot these days, generally pejoratively. For The Guardian, Nicola Davison writes one of the more useful backgrounders we’ve come across on where the term comes from and what the implications are when geologists (particularly stratigraphers) are dragged into social and political arguments about the future, rather than the knowable and relatively fixed stories of our past preserved in the rock layers. “Things that we’re living through at the moment – we don’t know how significant they are. [The Anthropocene] appears significant but it would be far easier if we were 200 to 300, possibly 2,000 to 3,000, years in the future and then we could look back and say: yes, that was the right thing to do.”

We’ve been hearing a lot of chatter about The Dark Forest Theory of the Internet, a thinkpiece from Yancey Strickler at Medium’s OneZero (their home this week for tech stuff). Strickler is considering our collective retreat from the public internet to more private channels—newsletters, Slack, WeChat, that sorta thing—which he sees as an understandable but potentially democratically and socially dangerous trend. It’s always seductive (and plays well on LinkedIn) when people drop their Big Named Theories (Strickler has not one but two of these in this piece), as it’s an easy way to paper over category errors and problematic thinking. If we (reductively) read Strickler correctly, he’s worried that if all the smart middle-aged people content themselves with newsletters and stop sharing their life milestones on the big platforms, all the poor idiots still on those platforms will be more vulnerable to exploitation by bad actors? Therefore limiting social engagement is abdicating responsibility? Our thought on this is—these things aren’t an either/or? We’ve always, as people, balanced different modes and scales of consumption and communication, and chosen our engagement accordingly. Private conversations, and the intimacy of the closed or self-selected group, aren’t modes of discourse which come at the expense of others, they’re just part of how we live. If anything, it’s the relatively recent new mode of the unfiltered mass firehose that we’re learning how to fit into those older ways, and retreat is not some rejection of a core clause of our social contract. Those still hooked on 90s-style utopian tech thinking still seem to believe that if only we could use the platforms better, if only people would stop doing it wrong, some perfect enlightenment is waiting on the other side. Also, grumpy folks opting out as they get older and choosing to move to the woods isn’t a trend, it’s also what we’ve always done. Maybe we should all get on TikTok and tell the kids what’s up.

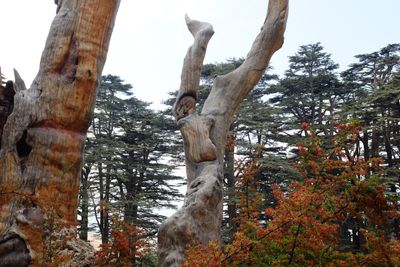

Anyway look here’s a long-thought-mythical petrified forest, excavated by storm.

About this time of year, every year, celery gets stupidly expensive down at the neighbourhood No Frills. This year the price hikes seemed to come quicker and last longer, and it turns out that of course it’s not some soffritto trend we’re not on top of—it’s the goddamn influencers.

Life in the Amazon warehouses is as fun as ever, and full of gamified opportunities to earn those Swag Bucks. Absolutely normal. “The games are showing some early signs of success at Amazon. Workers, who spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of reprisal from Amazon, said the games have indeed helped ease the tedium of the job…”

We dream so we can explore and prepare for the unexpected. Fiction works in similar ways, at a greater scale, allowing us to dream together. But as we fracture into ever more finely segmented audiences and interests, is this collective dream still possible? Maybe this story—that of our disintegration and our search for content that will bring us back to each other—is our shared story. If so, what greater creative achievement could there be than an elaborate yet generally applicable justification for one’s seemingly arbitrary taste for balancing Art snobbery and pop indulgence. “The only cure for too much fiction is good fiction.”

More Things

Behavioural ad targeting is big business, but it's not trickling down to publishers. Should they fight to reorient the industry around content—doubling down on the soft value of hard-earned audience trust—or get with the program and make an ad-tech play themselves?

“We should've known the war on sex was a lucrative growth market” with all the typical players including Google, Palantir, and the evangelical right.

A brief history of the audiobook from Lit Hub, which also catalogues a few little slivers of light sneaking past the black hole of that industry that is Audible.

We’re about 95% certain Pogo-sticks as a Service is some sort of marketing scam, but we’re enjoying thinking about how awful it is so very much, so we’re happy to be sucked in. We hope you are too! Not enough grazed knees on our city streets, we say.

We were devastated to hear that the poet Richard Siken suffered a serious stroke back in March. His unfathomably beautiful collection War of the Foxes is one of the most consistently returned-to books that we own. If his poems move you as they do us, perhaps think about contributing to his GoFundMe, set up by friends and colleagues?

To be a bird, or a flock of birds doing something together, one or many, starling or murmuration. To be a man on a hill, or all the men on all the hills, or half a man shivering in the flock of himself. These are some choices.

From Toronto, with love, we say:

.

And if you want to point your friends towards this here unknowable dark forest, here’s the map.