A FAIRY TALE

Once upon a time in a Toronto far away, there was a secret Facebook trading community named Bum’s Trading Zone. Bum’s was the sort of place where broke-ass inner-city kids would trade a half-ripe avocado for a subway token, or a haircut for a bag of weed. A place where whatever thing you had that you didn’t need, no matter how worthless, would find some kind of worth in somebody else’s pocket or lungs. Soon after it was founded, general internet tone policing saw it (rightly) change its name to Bunz. Which was fine and cute. We who write this email probably all invited each other to the “secret” group, and laughed together about the weirdo trades. The only rule of the place (other than the 30ish other rules) was that trades couldn’t involve cash. Resistance to capitalism amongst the broke-ass. Solidarity. Etc. Gift cards were ok though, which was kind of a huge loophole, but whatever. Meanwhile, as Vice articles about the secret club spread the word, the community grew and grew and grew, high up into the clouds, as more than 100,000 Torontonians, and eventually just as many in other towns, opted into the barter economy, resisted capitalism, bought each other gift cards, and tone policed each other into submission. A thousand Bunz flowers bloomed alongside, from Bunz Wedding Zone to Bunz Kombucha Zone, for all your scoby needs.

Who could blame the founder (sick of eating ramen) for trying to figure out how to make a living out of the joyful, sometimes joyless community she’d built in resistance to ordinary ways of making a living? Nobody, that’s who!

OMINOUS MUSIC PLAYS

Then, from far away, or from out of the woodwork, wherever, came the investors! Gotta be able to make money with that kind of user base! Somehow, soon, before you knew it, Bunz (the organisation) was no longer a Facebook community but a funded app, accelerating at scale, staffed up good and proper. Users wouldn’t trade for “stuff” any more, they’d trade for “BTZ”, pronounced Bitz, which was a cryptocurrency, but not a cryptocurrency in the sense of it actually being one. By which we mean, it was a big pile of points backed by nothing, allowing users to trade for slices of thin air, and trade that in at retailers who would subsequently invoice Bunz for money that would come from… somewhere. Whatever actual input streams of funds would come, they would come later. At crypto conferences, the organisation’s stumbling new CEO would declare that “we’re trying to parallel process this new technology stack with the user experience. We’re working on a number of strategies to manage that.”

What they’d really been selling were loyalty points. Paddy’s Dollars. Meanwhile, the original Facebook communities soldiered on under volunteer organisers, sort of connected but sort of not to this strange new startup that grew out of their ribs. And so it went on, users trading and accumulating balances of BTZ, retailers accepting them because why not,

And then, on a quiet September day, the “we made a difficult decision” post came from Bunz HQ, announcing staff layoffs and, more brutally, that the not-crypto BTZ would now only be accepted in small value transactions at cafes and food outlets (the sorts of places where they could still afford to pay up from dwindling cash reserves). Users? Stuck with worthless balances. The Facebook community? In open revolt. In joint statements, the community groups were no longer Bunz! They had defected! They were PALZ! As the Parkdale Life newsletter, another local institution amongst the broke-ass resisters of capitalism put it, Bunz had cancelled itself. The magic beans were just beans after all.

The only things left of any worth? That avocado, and the token you traded for it.

What’s the moral of our fairy tale? Is it something about good grassroots things being ruined by capital? Or about how creating something in resistance to the market and expecting to turn it into enterprise is always doomed to fail? Or is it that, as always, you should walk away very quickly from anybody who tries to solve a cashflow problem with crypto when they clearly don’t know what crypto is? It’s probably all of those things, but mostly? It’s that dumb groups where people trade half-deflated balloons for half-drunk bottles of wine should be allowed to exist, and sometimes all they need to be is that.

THINGS

The story of the iconic “Ghana Must Go” bag, as laid out by Shola Lawal in the South African Mail & Guardian, is a bloody mess of migration, expulsion, and xenophobia. As Lawal tells it, what was left behind back in the early 80s as people fled Nigeria with their possessions in those cheap chequered bags, with bats at their backs, is a troubled history that is still buried only just barely under the surface, unconfronted.

At The Atlantic, Bahar Gholipour digs into the back story of physiologist Benjamin Libet’s foundational study “disproving” the idea of free will, which has become a staple of both pop science podcasts and the sort of books that people like Yuval Noah Harari love to generate mountains of. As Gholipour, and more modern research, would have it, that entire study was based on a flawed premise. This is a great piece of science writing, and we don’t need peer reviews to agree with the newer, fuzzier suggestion that “the noisy activity in people’s brains sometimes happens to tip the scale if there’s nothing else to base a choice on, saving us from endless indecision when faced with an arbitrary task.” That feels… familiar to our noisy brains.

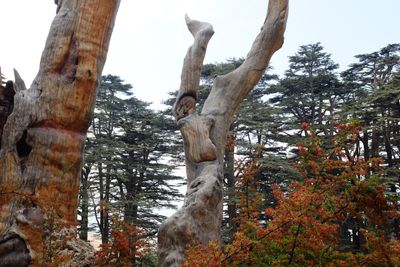

Around this time last year, your friendly BSer Patrick was just returning back from a month in the mountains of Tajikistan, where he’d decamped to thanks to a travel writing grant from mysterious fellow travellers Studio D Radiodurans. Together they’ve just published his account of part of his time there, in one of those old valleys. It’s mostly about what happens when the focus of history leaves a place behind, but also with a lot of walking, and sinking into hot springs, and only one mention of Rita Hayworth. He hopes you enjoy it. Patrick also guest-authored the Studio’s last newsletter, which is probably a good one to subscribe to if you like this one.

The breaking point for the climate doomists, apparently, is when Franzen joins them. Regular readers of this newsletter who pay attention to our existential crises might recognise that we often struggle to walk the line between realistically grappling with the catastrophe on the horizon (and closer now) and not giving into despair, rather trying (always trying) to figure out what it will be to live, and rebuild, in that new world we’re headed towards. We’d like to think we’re hopeful about humanity while pessimistic about grand fixes. This doesn’t mean laying down arms. It doesn’t mean giving up the fight. “We’re fucked anyway, so fuck it” is the sentiment of the least of us, and nobody we would waste our ever-more-precious oxygen on. Much of the response to Franzen was disingenuous and hyperbolic (as it always is to anything he utters, and we are not, generally, fans)—if you’ve only read the outrage and not his argument, you might not realise how uncontroversial it is, how undeserving of backlash it should be to try to find small models of resistance and coping within your own sphere of influence, when the broader and systemic is out of your grasp. But consider this—in Scientific American’s maturely titled discourse-appropriate post “Shut Up, Franzen”, climate scientist Kate Marvel concludes:“I am a scientist, which means I believe in miracles. I live on one. We are improbable life on a perfect planet. No other place in the Universe has nooks or perfect mountaintops or small and beautiful gardens. A flower in a garden is an exquisite thing, rooted in soil formed from old rocks broken by weather. It breathes in sunlight and carbon dioxide and conjures its food as if by magic. For the flower to exist, a confluence of extraordinary things must happen. It needs land and air and light and water, all in the right proportion, and all at the right time. Pick it, isolate it, and watch it wither. Flowers, like people, cannot grow alone.”

Of course that’s miraculous. Of course that’s where we find hope. In the small places. In how the small things grow into more beautiful things. The intangible and microscopic becomes the systemic. Meanwhile, the conclusion of Franzen’s piece reads:

“There may come a time, sooner than any of us likes to think, when the systems of industrial agriculture and global trade break down and homeless people outnumber people with homes. At that point, traditional local farming and strong communities will no longer just be liberal buzzwords. Kindness to neighbors and respect for the land—nurturing healthy soil, wisely managing water, caring for pollinators—will be essential in a crisis and in whatever society survives it. A project like the Homeless Garden offers me the hope that the future, while undoubtedly worse than the present, might also, in some ways, be better. Most of all, though, it gives me hope for today.”

To us it seems like nobody’s arguing other than the headline writers. Mary Annaïse Heglar, writing on Franzen and doomer dudes more generally in her piece “Home is Always Worth It”, is much more compelling in response, trying to find a middle ground as she argues again that everything we do matters and we have no time for nihilism. Is hoping for nuance in discourse as futile as hoping we stop at two degrees?

“It is absolutely possible to prepare for the disasters already, terrifyingly, upon us while also doing our damnedest to quit baking more in. We can acknowledge the storm of emotions that comes with watching our world unravel, process those emotions, and pick ourselves up to protect what we can. Because it’s worth it. Because we’re worth it. We don’t have to be pollyannish, or fatalistic. We can just be human. We can be messy, imperfect, contradictory, broken. We can recognize that ‘hopelessness’ does not mean ‘helplessness.’”

Meanwhile, we’ll just leave this here for you to read later, as that’s enough climate for this week, eh? The air conditioning trap: how cold air is heating the world.

In Logic, Hesper Desloovere Dixon on pregnancy tracking apps and the comfort, the dangers, and the unpaid labour of associated digital communities substituting for doctors who remain disinterested and out of reach.

Super-fun institutional politics from Maekan: “The International Council of Museums (ICOM) recently decided to postpone its decision to update the definition of a museum after a fierce debate between its members.”

Remember that scene in American Beauty where Ricky shows Jane a video of a floating plastic bag? Good. Now watch this.

TIFF wraps up this weekend in Toronto and, although we didn’t have enough time to create a thorough itinerary of everything buzzy, we did spend enough time in queues to feel part of the mix — our alternative to the annual summer-ending fair, The Ex. So we can’t provide a definitive guide, but we can make a couple recommendations. First, the Safdie brothers’ Uncut Gems. In Good Time, the Safdies used non-professional actors, a roughed-up A-list hunk, compassionate peeks into desperate lives, and a heartwarming story of brotherly love to propel the visceral and stylish thriller. The Safdies abandon these advantages in Uncut Gems, casting Adam Sandler as a desperate midtown diamond dealer starring opposite Kevin Durant as himself, in a role that is so much less of a cameo than anyone could have expected. Yet they still manage to build the same momentum and tension. We’re thrown into the middle of things—of so many things—and we’re barely able to keep up with the overlapping conversations, let alone the tangle of loans, bets, deals, and schemes. The Safdies work entirely for the screen, translating all internal conflict into action, and Uncut Gems makes it easy to imagine their impressionistic style making the leap from the art house. It’s no surprise then that international rights have been snatched up by Netflix, where audiences need to be re-hooked minute-by-minute.

Second, Yonfan’s No.7 Cherry Lane: think a Hong Kong version of Spirited Away which, rather than the world of spirits, takes place in the only somewhat less surreal (though more erotic and political) world of memory and dreams. The dialogue sometimes feels stilted, the animation sterile, and the characters alien and flat, but it’s all revealed to be part of the fun as the story lurches and shifts as it does in dreams.

Would an oral history of LonelyGirl15 make you feel old, or just make the internet feel old?

We’re still sad about Tuca and Bertie being cancelled, so here’s a beautiful little Vulture piece on one of its most surprisingly well-realised characters: An Ode to Speckle, a (Bird)Man for Our Times.

RIP Daniel Johnston, you beautiful goddam genius. If you’ve never watched The Devil and Daniel Johnston, do. Here’s a scene to get you started.